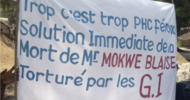

Dairy farmers Chris Gleeson, left, and Phil Bond inspect some calves on Bond's dairy farm in Taroon, west of Melbourne. Picture: Aaron Francis, Source: The Australian

Hungry in the food bowl

by Sue Neales

AUSTRALIAN farmers could be forgiven for feeling confused.

Every day they turn on the TV, open a newspaper or click on a tweet and are bombarded with politicians, international economists and global food security experts lauding agriculture as the cusp boom industry.

They hear messages exhorting farmers to double or treble their production by 2050 to meet the basic food needs of the world's nine billion hungry people.

The farm sector is told that guaranteed access to food - the ubiquitous hip phrase of food security - will be the key to every nation's future. That future world wars will be waged over sovereign ownership of fertile farms, food and water. And that Australia's continued economic prosperity, after the mining boom is over, will depend on agriculture and its ability to feed Asia's expanding middle class of 2.3 billion by 2030.

At the same time, the Chinese and Qatari governments are buying large Australian farms to produce food - sugar, wheat, sheep and dairy - much of it destined for their own people.

So, too, are Chinese private companies investing in Australian agriculture. Textile giant Shandong Ruyi last week completed its $240 million purchase of Australia's biggest cotton and irrigation property, Cubbie Station, while Shanghai Zhongfu last November was awarded the major government lease to further develop the $300m taxpayer-funded Ord irrigation project.

Massive US and global pension and investment funds such as Westchester, Laguna Bay and the giant US Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association pension fund's local agricultural arm, Global Ag Properties, are also on the Aussie farmland acquisition trail. And, in the US, legendary straw-hat, hay-chewing multi-billionaire Jim Rogers is urging shrewd investors to either go farming or buy luxury car dealerships in rural areas to service the millionaire farmers of the future.

But, in rural Australia, the hyperbole is not translating into practical benefits at the farm gate. Instead, discontent is growing at prices being paid to farmers for milk, fruit, vegetables, lamb and beef going "down, down, down" - to quote the slogan of supermarket colossus Coles.

Late last month, 600 angry dairy farmers gathered at a hall in sleepy Noorat in western Victoria and formed a new political action group, Farmer Power, in protest at their milk being sold at prices less than for bottled water.

"We are about letting people know who we are and about the plight of dairy farmers; we must have a fairer price for milk," says co-founder and Warrnambool dairyman Chris Gleeson.

Queensland cattleman Ian MacGibbon, of St Lawrence near Rockhampton, admits he finds all the future food bowl-boom hype bemusing, at best, and depressing the rest of the time.

Recent state government figures show the level of debt carried by Queensland farmers had jumped nearly 20 per cent in two years to $16.9 billion even before this week's horrendous floods.

Cattlemen such as MacGibbon are already carrying massive loans of an average of $1.4m each.

They live in hope of a better season. But, with the high Australian dollar pushing export demand down and Indonesia remaining stalwart in its halving of the live cattle quota, Meat and Livestock Australia is forecasting cattle prices to stagnate at their current low levels. Lamb prices have also fallen to four-year lows.

As further evidence of the beef industry's woes, Australia's largest cattle company and land owner, the Australian Agricultural Company, yesterday reported a $8m loss for this year.

Small wonder that land values for beef cattle stations are continuing to fall and rural confidence is slipping amid fears that nervous banks may start to call in loans.

"As always in all agriculture, the poor farmer is a price taker; you get what you are given and there is no negotiation," MacGibbon, a former Queensland state manager for specialist rural Rabobank, lamented yesterday.

"I haven't got any answers; you load your cattle or mung beans on the back of a truck after spending $100,000 producing them, and you have no power whatsoever. You might get $20,000 less than what it cost you to grow the beef or the beans - and there is nothing you can do about it."

MacGibbon says that with land values falling and no food boom or farm-gate price surge in sight, he finds it difficult to comprehend the strategy of the major global investment houses and pensions funds snapping up large parcels of prime Australian farmland.

"It's got me beat, these fellas coming in and investing. I really do not know what their thought pattern is because there is no way they are going to get a 6 per cent return on their investment each year, let alone a 10 per cent one," MacGibbon says. "So why they are doing it - for food, or in the hope land values will double in 20 years? To me it's the big unknown for these investors about where all of this will lead."

Victorian dairy farmer Marian Macdonald is just as fed up with what she sees as the yawning divide between her daily reality and the mixed messages being pitched far and wide about the bright future of agriculture.

"It's as confusing as all get-out, to tell you the truth, to keep hearing our leaders say that farmers are going to have to feed two billion more people, when we are not getting the price signals to encourage us to milk even one more cow," Macdonald says.

"What do we make of that? If we can't feed ourselves and our families first doing what we do, how can we be expected to feed anyone else? It's all very well for someone to say, 'You are carrying out a noble profession and helping feed the world', but the bank manager won't be swayed by that when it comes to reviewing our mortgages."

Macdonald says that, inside the gate of her Gippsland family farm and deep in mud, milk and 400 cows, the food security debate can seem very distant and unreal.

While the importance of global food security and boosted food production, drips from the lips of politicians Macdonald faces the prospect of an annual income hovering between zero and negative $20,000.

She reads, along with the rest of Australia's 115,000 farmers, how two of Australia's biggest and best tomato farmers last year went bust, unable to cope with falling prices, rising costs and the supermarket discounting war between Coles and Woolworths.

Tasmania's biggest grower of fresh carrots and onions, Premium Fresh, is in receivership while two of the nation's biggest strawberry and capsicum growers face collapse.

Then there are the apricot and peach growers struggling to survive as supermarket prices for fresh fruit hit rock bottom. Orange growers in Griffith are cutting down their trees again, unable to compete with cheap juice imports from Brazil.

Closer to home for Macdonald was the forecast by Dairy Australia that farm-gate prices for milk will fall a further 10 per cent this year because of supermarket milk discounting pressure and an oversupply of dairy products after three good seasons.

It's a price hit that Macdonald says she and her young family, who already rely on off-farm income, will strain to survive.

She ponders how long the Yarram dairy farm that has been in her family for generations can keep going, despite its good rainfall and productive pastures.

Small wonder, she says, that so many farms are up for sale and once-vibrant country towns are continuing to wither.

Macdonald, well-known via social media as the popular "Milk Maid Marian" blogger, blames the disconnect not just on global economists, politicians and fund managers for the paradox, but the increasingly popular world of urban foodies and aspiring Masterchefs.

The overriding big picture message being given to Australian farmers, says Macdonald, is that producing high-quality, healthy, nutritious and safe food efficiently is a rare and essential skill to be valued now - and treasured even more in the future by consumers and a grateful nation.

"But that's not the message I am getting down here on the farm via what we get paid for our produce," says a weary and confused Macdonald, facing further cuts this year to her milk price.

"Frankly, I'm getting fairly cranky with being told that food security and producing more food to feed the world is the big issue of our time, because right now we are just struggling to survive, with milk prices being pushed lower every season and consumers not seeming to care what the $1-a-litre milk price war is doing to farmers."

Paul Morris, chief executive of the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resources Economics and Sciences, says the gap is best explained as the clash between long-term global food trends and short-term price fluctuations.

But Morris says the fundamental premise of an approaching food boom, based on a 70 per cent leap in global food demand between 2010 and 2050, still held true.

"So what you are seeing is (global corporations) showing strong interest in investing in Australian land and agriculture because they are looking to the long term, where there are very good prospects for strong growth in (food) demand from Asia and price increases," Morris says.

"But that doesn't necessarily correlate with what the individual farmer is seeing because they are exposed to short-term prices which can vary wildly"

Near Cowra, Ed Fagan is best known as the vegetable farmer who was forced to plough tonnes of beautiful beetroot into the ground to rot because multinational conglomerate Heinz could import tins of beetroot from New Zealand more cheaply than he could produce it.

Fortunately for Fagan, entrepreneur and passionate Australian Dick Smith came to his rescue.

His Mulyan Farm now grows 100ha of beetroot, due to be harvested next month, supplying beetroot to both Smith's own brand and Coles' private label.

But it is an experience that has made Fagan cynical of the Asian food bowl talk and future food boom hype.

"I'm not holding my breath for this boom to happen; my father remembers in the 50s being told at a farming seminar that they would all be millionaires because the world would run out of food; well, he has not seen it and I can't see it happening in my time only," says Fagan, 38. "I not a pessimist, but I'm a realist, so if this food boom is really coming I have to ask why aren't these global investors or people who are telling us this stuff putting their money where there mouths are and building new food plants here to process this food and send it to Asia?

"It's not happening, and that's what makes me think it never will, because while we are among the most efficient farmers in the world in the tonnes we can grow per hectare or per hour of labour, we just can't compete with countries like New Zealand, the US or even the UK where labour costs are not $30 an hour like here but closer to $12 an hour."

The only answer Australian Farm Institute director Mick Keogh has for struggling farmers such as Fagan and Macdonald is to have patience and hang on.

Keogh says the future food bowl vision and the accompanying food boom will eventuate.

But with the Australian dollar so persistently high, Keogh admits Australia's farm exports will continue to find it tough going.

"In international terms, the prices of agricultural products are well above their 2007-08 (food crisis) high levels and are still trending upwards," Keogh said last night.

"But while commodity prices are high, at the farm gate here you have to take 30 per cent cent off that (because of the changing dollar value since the 1990s), so for food that is predominantly exported the Australian farmer is not seeing any benefit (of rising food prices) in his pocket."

Keogh acknowledges that the high Australian dollar does not account for the crisis facing all farmers. He says there is now solid evidence that in local markets, especially for milk, fresh fruit and vegetables, supermarket discount pressure has pushed prices paid to farmers down. And he cannot guarantee they will rise next week or even next year.

"But, despite that, the long-term rhetoric and forecasts are right. I think we will have (a food boom) and there is certainly no reason to change the (rosy) prospects for the five to 10-year outlook," Keogh says.

"But farmers can't be ordered to do anything; they can only respond to what the market is telling them and, right now, I agree that must be very hard for most of them to work out."