Mongabay| 19 November 2014

Palm oil interest surges in Papua New Guinea

by: John C. Cannon, mongabay.com correspondent

This article is the second in a three-part series that will examine the global impact of oil palm agriculture on local communities. Read the first part here.

As the lands of traditional palm oil powerhouses like Indonesia and Malaysia have become saturated with plantations, companies looking to profit have turned to vast areas of seemingly untouched tropical forest in other parts of the world – places like Papua New Guinea. But, in fact, say advocates of local communities, those forests often support the lives and livelihoods of millions of people who must have their rights taken into account.

In contrast to its neighbor on the western half of New Guinea Island – the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua – Papua New Guinea’s forests are surprisingly intact. According to Global Forest Watch data, 91 percent are classified as “primary,” meaning they show little evidence of human activity. By contrast, half of Indonesian New Guinea’s forests bear signs of human use. Both support about the same level of tree cover, at 95-96 percent.

As a result, palm oil producers have seen Papua New Guinea as ripe for exploitation in the drive to meet the demand for the world’s most popular vegetable oil. The crop actually has a long history in the country dating to the late 1800s, but interest in growing it on a large scale has picked up considerably in the past 10 years. That has some worried.

Just because the forests are classified as primary doesn’t mean they’re uninhabited, said Rosa Koian, information and communications coordinator with the Bismarck Ramu Group, an NGO that works to support rural communities and their rights throughout the country. On October 30, another group called the Rights and Resources Initiative published an analysis of more than 70,000 concessions for mining, agriculture, petrochemical drilling, and logging in tropical countries. They found that 93 percent were home to local and/or indigenous people.

“Eighty-five percent of Papua New Guineans are rural,” Koian said. “That means they depend on their land, their forests, their rivers and their seas for their survival.”

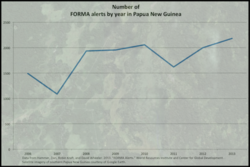

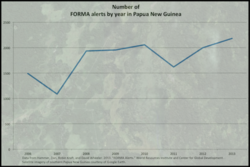

But that interest in developing oil palm plantations, as well as other types of agriculture, timber harvesting and mining, are affecting the forests. The entire country has seen a steady increase in what are known as FORMA alerts – semimonthly updates that use satellite imaging to identify spots likely to have recently been cleared.

In 2013, Papua New Guinea had nearly 2,200 alerts, the most since recordkeeping began in 2006, but 2014 is on pace to eclipse that mark by more than 20 percent. New Britain Island, part of Papua New Guinea and a focus for large-scale agriculture companies, will likely see a 30 percent increase in 2014 alerts compared to 2013.

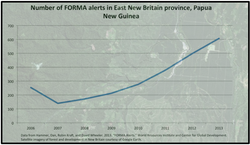

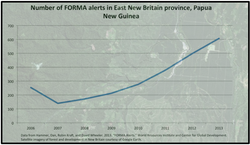

Koian said East New Britain province, about half of New Britain island, is of particular interest to developers. At the same time, FORMA alerts there are on the rise. The total number of alerts in 2013 for just the province was more than 600, 22 percent higher than 2012 and nearly 140 percent higher than 2006.

Koian argues that, to make matters worse, the local communities that have lived on these lands for millennia are losing their lands without fully understanding why or what they’ll get in return. “Proper processes are not followed, and very often landowners are tricked into signing papers,” she said. “They are often promised lots of money, nice houses, good roads and overseas trips,” but little of that ever materializes, she added.

"Most of these communities have customary systems of land management. These are under threat, and they’re being ignored,” said Devlin Kuyek, a researcher with the NGO GRAIN. Kuyek and his colleagues recently authored a report looking at the effects of surging global industrial palm oil agriculture on local economies and communities.

While Kuyek argued that some international firms ignore countries’ laws, others say that their success is inextricably linked with local populations. “In Papua New Guinea land and people are so intertwined,” said Simon Lord, group director of sustainability for New Britain Palm Oil, which produces palm oil in the country. “If a company fails to appreciate the customary and user rights of the people then ultimately the project will fail.”

Communication between the company and community is essential, Lord said. “FPIC (Free, prior, and informed consent) is not a ‘one off ‘ exercise and done properly it takes time and requires patience,” he added. FPIC is a core tenet of the RPSO, meant to ensure that populations are involved in and understand the ramifications of allowing their land to be used for oil palm agriculture. “The only way for this to happen is if it is done in situ at the village level and with the participation of the entire community and the company.”

The need for community involvement is particularly important given a recent push from the government of Papua New Guinea to open up lands to industrial conversion. Kuyek and his colleagues note that the government has set a goal to diminish customary ownership of land from 97 percent in 2009 to 80 percent by 2030; it’s already down to 85 percent. And Kuyek also said this trend isn’t exclusive to Papua New Guinea. Developing countries around the world are facing similar pressure from the international community to do the same in an effort to encourage economic growth.

That strategy doesn’t sit well with Rosa Koian. In her view, “We will never reduce poverty if thousands of land-, forest-, river- and sea-dependent people are forced off their land. They lose their food supply system and everything fails with it.”

There is also evidence that companies may be taking advantage of the surging interest in palm oil to get to the country’s timber reserves. A 2013 study by researchers at James Cook University in Australia found that only five of thirty-six oil palm proposed concessions were likely to be developed. The authors believed that many companies are feigning interest in establishing oil palm agriculture to sidestep restrictions on logging in the country.

Interestingly, Papua New Guineans have had success challenging the legal validity of some of the leases that have given their land to foreign companies. In a recent blog post for the Rainforest Action Network, a farmer named Lester Seri explained that while he and his neighbors have managed to get leases of their land reversed, a corporation called Kuala Lumpur Kepong Berhard has apparently refused to vacate one of the spots in question.

He points out that the Malaysian palm oil company is a member of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and these forests in Oro Province are of “high conservation value,” and as such, “There is absolutely no reason for them still to be here, yet they are.” Mongabay.com has been in touch with a representative of Kuala Lumpur Kepong Berhard, but they thus far have offered no comment on this issue or their interests in Papua New Guinea.

Koian sees hope in the country’s legal system and the fact that Papua New Guineans still by and large own the land they live on. In addition, they do have a champion in Oro Governor Gary Juffa. Oro Province is a focal point for other companies looking for development opportunities, Koian said.

“When it comes to land grabbing, Governor Juffa is the only parliamentarian openly standing up to the loggers and palm oil developers in his province.” Before thinking about the interests of those outside the country, she added, “Government officials need to respect first their own people – the people of Papua New Guinea.”

Citations:

Hammer, Dan, Robin Kraft, and David Wheeler. 2013. “FORMA Alerts.” World Resources Institute and Center for Global Development. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on 30 October 2014. www.globalforestwatch.org.

Palm oil interest surges in Papua New Guinea

by: John C. Cannon, mongabay.com correspondent

This article is the second in a three-part series that will examine the global impact of oil palm agriculture on local communities. Read the first part here.

As the lands of traditional palm oil powerhouses like Indonesia and Malaysia have become saturated with plantations, companies looking to profit have turned to vast areas of seemingly untouched tropical forest in other parts of the world – places like Papua New Guinea. But, in fact, say advocates of local communities, those forests often support the lives and livelihoods of millions of people who must have their rights taken into account.

In contrast to its neighbor on the western half of New Guinea Island – the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua – Papua New Guinea’s forests are surprisingly intact. According to Global Forest Watch data, 91 percent are classified as “primary,” meaning they show little evidence of human activity. By contrast, half of Indonesian New Guinea’s forests bear signs of human use. Both support about the same level of tree cover, at 95-96 percent.

As a result, palm oil producers have seen Papua New Guinea as ripe for exploitation in the drive to meet the demand for the world’s most popular vegetable oil. The crop actually has a long history in the country dating to the late 1800s, but interest in growing it on a large scale has picked up considerably in the past 10 years. That has some worried.

Just because the forests are classified as primary doesn’t mean they’re uninhabited, said Rosa Koian, information and communications coordinator with the Bismarck Ramu Group, an NGO that works to support rural communities and their rights throughout the country. On October 30, another group called the Rights and Resources Initiative published an analysis of more than 70,000 concessions for mining, agriculture, petrochemical drilling, and logging in tropical countries. They found that 93 percent were home to local and/or indigenous people.

“Eighty-five percent of Papua New Guineans are rural,” Koian said. “That means they depend on their land, their forests, their rivers and their seas for their survival.”

But that interest in developing oil palm plantations, as well as other types of agriculture, timber harvesting and mining, are affecting the forests. The entire country has seen a steady increase in what are known as FORMA alerts – semimonthly updates that use satellite imaging to identify spots likely to have recently been cleared.

In 2013, Papua New Guinea had nearly 2,200 alerts, the most since recordkeeping began in 2006, but 2014 is on pace to eclipse that mark by more than 20 percent. New Britain Island, part of Papua New Guinea and a focus for large-scale agriculture companies, will likely see a 30 percent increase in 2014 alerts compared to 2013.

Koian said East New Britain province, about half of New Britain island, is of particular interest to developers. At the same time, FORMA alerts there are on the rise. The total number of alerts in 2013 for just the province was more than 600, 22 percent higher than 2012 and nearly 140 percent higher than 2006.

FORMA alerts, 2006-2014, showing areas of likely forest loss in East Britain Province (outlined in green), Papua New Guinea. East Britain has seen a surge in development interest from international companies. Map courtesy of Global Forest Watch.

The number of annual FORMA alerts per year in East New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea. The total in 2013 was 140 percent higher than in 2006.

FORMA alerts showing probable forest lost on a twice-monthly basis have been steadily rising, and 2014 is on pace to have the most alerts since recording began in 2006.

Koian argues that, to make matters worse, the local communities that have lived on these lands for millennia are losing their lands without fully understanding why or what they’ll get in return. “Proper processes are not followed, and very often landowners are tricked into signing papers,” she said. “They are often promised lots of money, nice houses, good roads and overseas trips,” but little of that ever materializes, she added.

"Most of these communities have customary systems of land management. These are under threat, and they’re being ignored,” said Devlin Kuyek, a researcher with the NGO GRAIN. Kuyek and his colleagues recently authored a report looking at the effects of surging global industrial palm oil agriculture on local economies and communities.

While Kuyek argued that some international firms ignore countries’ laws, others say that their success is inextricably linked with local populations. “In Papua New Guinea land and people are so intertwined,” said Simon Lord, group director of sustainability for New Britain Palm Oil, which produces palm oil in the country. “If a company fails to appreciate the customary and user rights of the people then ultimately the project will fail.”

Communication between the company and community is essential, Lord said. “FPIC (Free, prior, and informed consent) is not a ‘one off ‘ exercise and done properly it takes time and requires patience,” he added. FPIC is a core tenet of the RPSO, meant to ensure that populations are involved in and understand the ramifications of allowing their land to be used for oil palm agriculture. “The only way for this to happen is if it is done in situ at the village level and with the participation of the entire community and the company.”

The need for community involvement is particularly important given a recent push from the government of Papua New Guinea to open up lands to industrial conversion. Kuyek and his colleagues note that the government has set a goal to diminish customary ownership of land from 97 percent in 2009 to 80 percent by 2030; it’s already down to 85 percent. And Kuyek also said this trend isn’t exclusive to Papua New Guinea. Developing countries around the world are facing similar pressure from the international community to do the same in an effort to encourage economic growth.

That strategy doesn’t sit well with Rosa Koian. In her view, “We will never reduce poverty if thousands of land-, forest-, river- and sea-dependent people are forced off their land. They lose their food supply system and everything fails with it.”

There is also evidence that companies may be taking advantage of the surging interest in palm oil to get to the country’s timber reserves. A 2013 study by researchers at James Cook University in Australia found that only five of thirty-six oil palm proposed concessions were likely to be developed. The authors believed that many companies are feigning interest in establishing oil palm agriculture to sidestep restrictions on logging in the country.

Interestingly, Papua New Guineans have had success challenging the legal validity of some of the leases that have given their land to foreign companies. In a recent blog post for the Rainforest Action Network, a farmer named Lester Seri explained that while he and his neighbors have managed to get leases of their land reversed, a corporation called Kuala Lumpur Kepong Berhard has apparently refused to vacate one of the spots in question.

He points out that the Malaysian palm oil company is a member of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and these forests in Oro Province are of “high conservation value,” and as such, “There is absolutely no reason for them still to be here, yet they are.” Mongabay.com has been in touch with a representative of Kuala Lumpur Kepong Berhard, but they thus far have offered no comment on this issue or their interests in Papua New Guinea.

Koian sees hope in the country’s legal system and the fact that Papua New Guineans still by and large own the land they live on. In addition, they do have a champion in Oro Governor Gary Juffa. Oro Province is a focal point for other companies looking for development opportunities, Koian said.

“When it comes to land grabbing, Governor Juffa is the only parliamentarian openly standing up to the loggers and palm oil developers in his province.” Before thinking about the interests of those outside the country, she added, “Government officials need to respect first their own people – the people of Papua New Guinea.”

Citations:

Hammer, Dan, Robin Kraft, and David Wheeler. 2013. “FORMA Alerts.” World Resources Institute and Center for Global Development. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on 30 October 2014. www.globalforestwatch.org.