Mongabay| 23 December 2014

Palawan palm oil presence likely to grow, industry rep denies harmful impact

by Shaira Panela, mongabay.com correspondent

by Shaira Panela, mongabay.com correspondent

This is the second part in a two-part series examining the planned expansion of palm oil production on the island of Palawan. Read the first part here

Plans to convert eight million hectares of land for palm oil production on Palawan island in the Philippines have been met with opposition from environmental and social advocacy groups, with a petition to cease development sent to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights by an anti-palm oil expansion group. But an industry representative denies claims that all eight million hectares will be cultivated to the detriment of wildlife and human communities, maintaining palm oil expansion will be beneficial to the people of Palawan.

The current oil palm expansion project is overseen by Palawan Palm & Vegetable Oil Mills, Inc. (PPVOMI), and Agumil Philippines, Inc. (AGPI). Both companies have only partial Philippine ownership, with PPVOMI 60 percent Singapore-owned and AGPI 25 percent Malaysia-owned, according to the SEI paper.

C.K. Chang, who represents PPVOMI and AGPI, said even though it may be possible to grow oil palm on approximately 200,000 hectares (ha) in Palawan, in reality only a fraction of that is developable.

"If you have seen the aerial data, most of the parts in that 200,000 ha are protected areas, some parts are hills which require terracing and building of roads which is costly to develop," Chang told mongabay.com. He added that the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) permit they received only allows them to develop up to 15,000 hectares.

A working paper released by the Sweden-based Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) earlier this year, showing the extent and implication of the growing palm oil industry in Palawan. According to the paper, six towns have seen the expansion of oil palm plantations. These include Aborlan, Bataraza, Brooke’s Point, Rizal, Quezon, and Sofronio Española. The paper states palm oil concessions occupy up to 99 percent of the total amount of agricultural land in southern Palawan.

Government staff in Puerto Princesa City, Palawan’s capital, disclosed that foreign investors coming from Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, China and Japan are looking into acquiring agricultural lands in the province, according to the SEI paper.

“Altogether, the Provincial Agriculturist Office receives 15–20 requests per year from agricultural investors hoping for government support. Beyond the existing palm oil project, informal estimates suggest that between 10,000 and 20,000 ha of new land may have already been acquired for oil palm plantations, including for the establishment of new mill(s),” states the paper.

Palawan is deemed an ideal location for growing oil palm for a number of reasons: it is relatively accessible, land is affordable, and the population is peaceful—especially compared with conflict-laden Mindanao, where much of the country’s oil palm cultivation occurs. In addition, the town of Brooke’s Point where the Palawan oil palm mill is located has an international port that facilitates easy shipping and trade.

Meanwhile, the provincial government recorded at least 14 smallholder palm oil growing cooperatives and two other oil palm cultivation operations in 2013, all of which are bound by contracts to deliver fresh bunches of oil palm fruit to PPVOMI. The SEI paper also showed that many members of the cooperatives are migrant settlers while the laborers on the plantation are indigenous people who complain of unfair labor practices.

But the biggest problem faced by indigenous people in Palawan is land encroachment as the plantations expand.

A tribal farmer in Brooke’s Point was quoted in the SEI paper as saying, “The company is still expanding… burial grounds [are] cultivated with oil palm… herbal plants and trees normally used by native doctors are cut… bamboos, trees, vines for daily life and wild fruits and materials for houses are cut or bulldozed.”

According to the paper, some members in cooperatives were disqualified from entering the out-grower scheme for failing to provide land titles to the plots they volunteered to be cultivated for oil palm.

These complaints have been the basis for a petition for a moratorium by various indigenous people’s rights groups and advocates, including CALG.

For their part, AGPI staff recognized they need to review its means of land acquisition. In the SEI paper, an AGPI staff member admitted the company made mistakes, taking advantage of loopholes and selling land as “informal realty,” adding that “in some cases people were rightful owners, for instance indigenous peoples, but couldn’t sell since the land was ancestral domains…[in other cases] they were not the rightful owners.”

But a representative of the Palawan provincial government pointed his finger to the National Council on Indigenous People (NCIP), asserting that it was the one responsible in securing the ancestral domains of the tribes.

Meanwhile, Chang told mongabay.com that PPVOMI and AGPI do not encroach into tribal lands because they cannot develop without clearance from NCIP, DENR, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Agricultural Reform (DAR), and local government units. He maintained that the companies’ presence is benefiting the populace of Palawan.

"We are actually helping southern Palawan to solve its poverty problem. We are helping farmers... We help develop even the Muslim areas in Bataraza... We do not encroach their lands," he said.

CALG said in a statement that even the NCIP—the government agency tasked to protect the rights of the tribesmen—is slow in protecting them from the encroachment of oil palm plantations in their area.

The SEI paper noted, “the provincial government appears to have placed itself in a somewhat difficult position by promoting the oil palm industry without clear terms of reference or regulatory environment. This has made it more challenging to define the responsibilities of Agumil, further complicated when provincial offices of national government agencies ceased involvement and the project became a solely private undertaking. While it has the mandate to oversee the implementation of the national policy on oil palm, the PCA in Puerto Princesa lacks guidelines for implementation that would clarify its regulatory role.”

Furthermore, the SEI study recommends the land grabbing issue should be taken up by the NCIP, DENR and DAR together to adequately address the concerns of Palawan residents and ensure their wellbeing, as well as that of the environment.

“The palm oil sector, like other large-scale agro-industries, is often promoted with a promise of economic benefits to cash-strapped local governments and landowners looking to improve limited livelihood opportunities,” states the paper. “Meanwhile, any large-scale land conversion and centralization of productive control carries social and environmental risks.

“Questions arise as to the net benefits of the changes in land use, the creation of winners and losers in local communities, and whether institutions are equipped to manage the agro-industry and safeguard the interests of local communities, other stakeholders, and citizens in general.”

Citations:

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland, Google, USGS, and NASA. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Dec. 23, 2014. www.globalforestwatch.org.

Palawan palm oil presence likely to grow, industry rep denies harmful impact

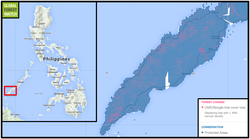

The brunt of the current palm oil expansion plans will affect the southern portion of Palawan, which lost more than 600,000 hectares of tree cover from 2001 through 2012 despite most of the island's designated as a protected area, according to Global Forest Watch.

This is the second part in a two-part series examining the planned expansion of palm oil production on the island of Palawan. Read the first part here

Plans to convert eight million hectares of land for palm oil production on Palawan island in the Philippines have been met with opposition from environmental and social advocacy groups, with a petition to cease development sent to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights by an anti-palm oil expansion group. But an industry representative denies claims that all eight million hectares will be cultivated to the detriment of wildlife and human communities, maintaining palm oil expansion will be beneficial to the people of Palawan.

The current oil palm expansion project is overseen by Palawan Palm & Vegetable Oil Mills, Inc. (PPVOMI), and Agumil Philippines, Inc. (AGPI). Both companies have only partial Philippine ownership, with PPVOMI 60 percent Singapore-owned and AGPI 25 percent Malaysia-owned, according to the SEI paper.

C.K. Chang, who represents PPVOMI and AGPI, said even though it may be possible to grow oil palm on approximately 200,000 hectares (ha) in Palawan, in reality only a fraction of that is developable.

"If you have seen the aerial data, most of the parts in that 200,000 ha are protected areas, some parts are hills which require terracing and building of roads which is costly to develop," Chang told mongabay.com. He added that the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) permit they received only allows them to develop up to 15,000 hectares.

A working paper released by the Sweden-based Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) earlier this year, showing the extent and implication of the growing palm oil industry in Palawan. According to the paper, six towns have seen the expansion of oil palm plantations. These include Aborlan, Bataraza, Brooke’s Point, Rizal, Quezon, and Sofronio Española. The paper states palm oil concessions occupy up to 99 percent of the total amount of agricultural land in southern Palawan.

Government staff in Puerto Princesa City, Palawan’s capital, disclosed that foreign investors coming from Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, China and Japan are looking into acquiring agricultural lands in the province, according to the SEI paper.

“Altogether, the Provincial Agriculturist Office receives 15–20 requests per year from agricultural investors hoping for government support. Beyond the existing palm oil project, informal estimates suggest that between 10,000 and 20,000 ha of new land may have already been acquired for oil palm plantations, including for the establishment of new mill(s),” states the paper.

Palawan is deemed an ideal location for growing oil palm for a number of reasons: it is relatively accessible, land is affordable, and the population is peaceful—especially compared with conflict-laden Mindanao, where much of the country’s oil palm cultivation occurs. In addition, the town of Brooke’s Point where the Palawan oil palm mill is located has an international port that facilitates easy shipping and trade.

Meanwhile, the provincial government recorded at least 14 smallholder palm oil growing cooperatives and two other oil palm cultivation operations in 2013, all of which are bound by contracts to deliver fresh bunches of oil palm fruit to PPVOMI. The SEI paper also showed that many members of the cooperatives are migrant settlers while the laborers on the plantation are indigenous people who complain of unfair labor practices.

But the biggest problem faced by indigenous people in Palawan is land encroachment as the plantations expand.

A tribal farmer in Brooke’s Point was quoted in the SEI paper as saying, “The company is still expanding… burial grounds [are] cultivated with oil palm… herbal plants and trees normally used by native doctors are cut… bamboos, trees, vines for daily life and wild fruits and materials for houses are cut or bulldozed.”

According to the paper, some members in cooperatives were disqualified from entering the out-grower scheme for failing to provide land titles to the plots they volunteered to be cultivated for oil palm.

These complaints have been the basis for a petition for a moratorium by various indigenous people’s rights groups and advocates, including CALG.

For their part, AGPI staff recognized they need to review its means of land acquisition. In the SEI paper, an AGPI staff member admitted the company made mistakes, taking advantage of loopholes and selling land as “informal realty,” adding that “in some cases people were rightful owners, for instance indigenous peoples, but couldn’t sell since the land was ancestral domains…[in other cases] they were not the rightful owners.”

But a representative of the Palawan provincial government pointed his finger to the National Council on Indigenous People (NCIP), asserting that it was the one responsible in securing the ancestral domains of the tribes.

Meanwhile, Chang told mongabay.com that PPVOMI and AGPI do not encroach into tribal lands because they cannot develop without clearance from NCIP, DENR, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Agricultural Reform (DAR), and local government units. He maintained that the companies’ presence is benefiting the populace of Palawan.

"We are actually helping southern Palawan to solve its poverty problem. We are helping farmers... We help develop even the Muslim areas in Bataraza... We do not encroach their lands," he said.

CALG said in a statement that even the NCIP—the government agency tasked to protect the rights of the tribesmen—is slow in protecting them from the encroachment of oil palm plantations in their area.

The SEI paper noted, “the provincial government appears to have placed itself in a somewhat difficult position by promoting the oil palm industry without clear terms of reference or regulatory environment. This has made it more challenging to define the responsibilities of Agumil, further complicated when provincial offices of national government agencies ceased involvement and the project became a solely private undertaking. While it has the mandate to oversee the implementation of the national policy on oil palm, the PCA in Puerto Princesa lacks guidelines for implementation that would clarify its regulatory role.”

Furthermore, the SEI study recommends the land grabbing issue should be taken up by the NCIP, DENR and DAR together to adequately address the concerns of Palawan residents and ensure their wellbeing, as well as that of the environment.

“The palm oil sector, like other large-scale agro-industries, is often promoted with a promise of economic benefits to cash-strapped local governments and landowners looking to improve limited livelihood opportunities,” states the paper. “Meanwhile, any large-scale land conversion and centralization of productive control carries social and environmental risks.

“Questions arise as to the net benefits of the changes in land use, the creation of winners and losers in local communities, and whether institutions are equipped to manage the agro-industry and safeguard the interests of local communities, other stakeholders, and citizens in general.”

Citations:

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland, Google, USGS, and NASA. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Dec. 23, 2014. www.globalforestwatch.org.