Sunday, April 4, 2010

News photo

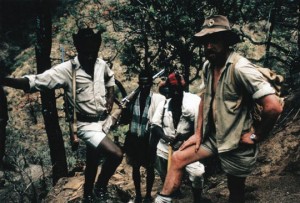

Active duty: Young Nic (right) on patrol while serving as a Game Warden in the Simien Mountains of northern Ethiopia in the late 1960s. The man on the left, with a rifle slung over his shoulder, was Assistant Warden Mesfin Abebe, and the two men behind were local vigilantes who joined us in pursuit of illegal loggers. C.W. NICOL PHOTOS

OLD NIC'S NOTEBOOK

Japan, please don't go grabbing Ethiopians' land

Reflections on feelings and farmland born of an exciting time spent serving Haile Selassie

By C.W. NICOL

On March 15 just gone, this newspaper carried an excellent but disturbing article by John Vidal, environment editor of the London-based Guardian newspaper. He wrote about food shortages and land-grabbing in Africa, and I was particularly troubled to read about deals going on to sell Ethiopian land to foreign investors. In the article, an Ethiopian government spokesperson was quoted as saying that "Ethiopia has 74 million hectares of fertile land, of which only 15 percent is currently in use — mainly by subsistence farmers . . . "

News photo

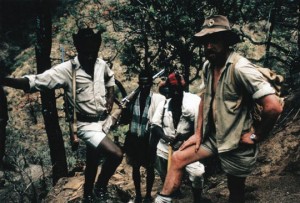

High tea: Senior Game Warden John Blower (right) takes a break and looks forward to a well-earned cuppa in a spectacular setting among the towering Simien Mountains. At the time, we were on one of our boundary-mapping treks that led to an Imperial proclamation in 1969 establishing the Simien Mountain National Park precisely within the area we had suggested.

From September 1967 until October 1969 I was the first Game Warden of what was soon to become the Simien Mountain National Park in the northern mountains of Begemdir province in Ethiopia — a 220-sq.-km expanse that was enshrined in law with a proclamation by His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie printed in the Negarit Gazeta newspaper on Oct. 31, 1969. That proclamation defined the park's boundaries as those mapped out by myself and Senior Game Warden John Blower, the Addis Ababa-based Brit who was the boss of all the country's game wardens.

At the time, of course, that was encouraging news, soon after I left Ethiopia I started hearing about more wild land being plowed up, more forests cut down and — almost daily — rifle shots heard around the great Simien escarpment, home to the endangered walia ibex.

I had departed Ethiopia with a heavy heart, knowing it was heading for more chaos and internal strife, large-scale land erosion, loss of forests and wildlife — and inevitably, mass starvation.

Together with my very able assistant, Mesfin Abebe, a graduate of the Tanzanian College of Wildlife Management, and our 20 rangers, we had fought and struggled for two years to establish the park. We had done our best to deal with poachers, hill bandits, illegal loggers and illegal farming on vulnerable watershed slopes, all made worse by rampant corruption — from local governors and police to senior officials in our own central wildlife department.

Towards the end of my sojourn in Ethiopia, I drove the 800 km or so to the capital, Addis Ababa, for meetings about the new park boundaries. The city was in chaos. The university and nine secondary schools were closed. Truckloads of soldiers and police were everywhere and I saw jeeps mounted with 50-calibre machine guns. The students were not allowed to gather, even in small groups, and hundreds had been arrested. Wild rumors were heard and repeated — there was going to be a coup d'etat . . . some students had been thrown into a cesspit and drowned by the Imperial guard . . . the army was poised outside the city, ready to come in and take over . . . five young people had been jailed for five years for distributing pamphlets . . . all foreigners would be killed.

On that particular visit, I myself — with a machete in one hand and a Walther PPK in the other — faced down a vengeful mob as I was driving along a lonely, muddy track on the outskirts of the city. Two Ethiopian students of English tried to reason with the mob, saying that I was helping the country, but the mob wanted blood. I was pretty angry, and a bit of a wild man at that age, so after firing a couple of shots in the air, I tossed the machete onto the seat beside me, stuck the pistol in my belt, then quickly collared two rabble-rousers (as a Game Warden I had the rights to search, seize and arrest) and hurled them into the back of the vehicle. The people in front had to either scatter or get run down, but about 50 screaming men and boys chased after my vehicle, throwing stones and waving knives, machetes and sticks.

Why the fuss? I couldn't think of anything I'd done or said to get them so enraged, but I was a foreigner and all foreigners were suspect during that nervous time. I drove the captives to a hospital, had them checked out so they couldn't later claim I had run them down or something. Getting money out of scared foreigners that way was a minor industry back then in Addis Ababa.

If that wasn't enough, a friend from the Israeli embassy later told me that I was marked for assassination. An attempt had already been made on my life in Gondar, the old castled city and provincial capital of Begemdir, where I sent off reports to the capital and picked up supplies and wages for park staff and workers.

One night, walking back to my hotel from a bar along an unlit, deserted lane, two men came at me from behind wielding iron-tipped clubs. Thanks to my karate skills I was able to fight it out without drawing my pistol. After the skirmish I returned to my hotel to bandage up the wounds on my hand and forearm. The next morning, as I was having breakfast and getting ready to return to the park, a student I was friendly with came to the hotel and told me that, just after the fight, a police Land Rover drove up the lane with its lights out and officers dragged the two attackers I had left lying on the ground to the vehicle, tossed them into the back, and drove off. Later, other witnesses told me the police had driven the men beyond the city limits and dumped them in a field outside the local slaughterhouse, a place that attracted hungry hyenas.

On my next visit to Gondar, when I made inquiries to the police about the incident they claimed to have known nothing. This was not surprising, as the Chief of Police was involved in the illegal wild-animal fur trade, which we had been disrupting. That unsavory gentleman had already warned me to stay away from fur traders. I told him that as I was a Game Warden, it was my job not only to protect the park but also to find and arrest such criminals.

When I got back to Gondar from Addis Ababa after the park boundary meetings there were riots there too. A police Land Rover had been burned. Police with guns faced the students. At night, they dragged students out of their houses and beat them with clubs while their parents watched and pleaded for them. A couple of bright young men whom I knew vanished.

Then there were the anti-Arab riots.

The Eritrean Liberation Front had been blowing up planes and generally making a nuisance of themselves, and there had been reports in the press about links with Syria. A huge "spontaneous" anti-Arab parade was held in Addis Ababa, with Amhara warriors wearing their lion-mane headdresses, carrying round shields and curved scimitars. In cities and villages all over Ethiopia, Arabs were beaten up and their shops were stoned or even looted.

At that time, several cultured Ethiopians came to me, asking if I could get guns and ammunition for them. (Of course I could, but would not.)

I cannot imagine now, in 2010, that Ethiopians have changed so much that they will stay subdued and silent while being displaced from their land by foreign investors. I especially fear that the Amhara, who are Coptic Christians, will be incensed if Arab Muslims are involved in any moves to take away their land rights. The Amhara are an especially proud and ancient people. It was ordinary Ethiopians, many of them barefooted and lightly armed, who finally drove out the Italian invaders in 1941, despite their machine guns, howitzers, planes and tanks.

Nothing I can do or say will change any of this, but even so I, with deep respect for Ethiopians — and as a citizen of this country — urge Japan not to join in this greedy scrabble. We have far too much arable land going to waste here in Japan. Land and food is not only a question of money. People who live off their land feel deeply about it, no matter how poor and defenceless they may seem.

Japan should shun this new kind of colonization like a plague, no matter what well-paid city-based officials may say. As other people who have lived and worked in the country have noted, I can myself affirm a strong belief that there is no land in Ethiopia that has no owners or users.

Back in the late 1960s, we had enough problems establishing a national park, one in which farmers were allowed to keep on using their land. We tried to stop poachers and illegal loggers, and that was not easy. I doubt if we would have survived if we had tried to take the locals' land from them — even if it was for reasons of wildlife protection or water conservation.

Japan, please, by all means help poor African farmers — but do not have anything to do with displacing them!

Active duty: Young Nic (right) on patrol while serving as a Game Warden in the Simien Mountains of northern Ethiopia in the late 1960s. The man on the left, with a rifle slung over his shoulder, was Assistant Warden Mesfin Abebe, and the two men behind were local vigilantes who joined us in pursuit of illegal loggers. C.W. NICOL PHOTOS

Japan Times | Sunday, April 4, 2010

Reflections on feelings and farmland born of an exciting time spent serving Haile Selassie

By C.W. NICOL

On March 15 just gone, this newspaper carried an excellent but disturbing article by John Vidal, environment editor of the London-based Guardian newspaper. He wrote about food shortages and land-grabbing in Africa, and I was particularly troubled to read about deals going on to sell Ethiopian land to foreign investors. In the article, an Ethiopian government spokesperson was quoted as saying that "Ethiopia has 74 million hectares of fertile land, of which only 15 percent is currently in use — mainly by subsistence farmers . . . "

From September 1967 until October 1969 I was the first Game Warden of what was soon to become the Simien Mountain National Park in the northern mountains of Begemdir province in Ethiopia — a 220-sq.-km expanse that was enshrined in law with a proclamation by His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie printed in the Negarit Gazeta newspaper on Oct. 31, 1969. That proclamation defined the park's boundaries as those mapped out by myself and Senior Game Warden John Blower, the Addis Ababa-based Brit who was the boss of all the country's game wardens.

At the time, of course, that was encouraging news, soon after I left Ethiopia I started hearing about more wild land being plowed up, more forests cut down and — almost daily — rifle shots heard around the great Simien escarpment, home to the endangered walia ibex.

I had departed Ethiopia with a heavy heart, knowing it was heading for more chaos and internal strife, large-scale land erosion, loss of forests and wildlife — and inevitably, mass starvation.

High tea: Senior Game Warden John Blower (right) takes a break and looks forward to a well-earned cuppa in a spectacular setting among the towering Simien Mountains. At the time, we were on one of our boundary-mapping treks that led to an Imperial proclamation in 1969 establishing the Simien Mountain National Park precisely within the area we had suggested.

Together with my very able assistant, Mesfin Abebe, a graduate of the Tanzanian College of Wildlife Management, and our 20 rangers, we had fought and struggled for two years to establish the park. We had done our best to deal with poachers, hill bandits, illegal loggers and illegal farming on vulnerable watershed slopes, all made worse by rampant corruption — from local governors and police to senior officials in our own central wildlife department.

Towards the end of my sojourn in Ethiopia, I drove the 800 km or so to the capital, Addis Ababa, for meetings about the new park boundaries. The city was in chaos. The university and nine secondary schools were closed. Truckloads of soldiers and police were everywhere and I saw jeeps mounted with 50-calibre machine guns. The students were not allowed to gather, even in small groups, and hundreds had been arrested. Wild rumors were heard and repeated — there was going to be a coup d'etat . . . some students had been thrown into a cesspit and drowned by the Imperial guard . . . the army was poised outside the city, ready to come in and take over . . . five young people had been jailed for five years for distributing pamphlets . . . all foreigners would be killed.

On that particular visit, I myself — with a machete in one hand and a Walther PPK in the other — faced down a vengeful mob as I was driving along a lonely, muddy track on the outskirts of the city. Two Ethiopian students of English tried to reason with the mob, saying that I was helping the country, but the mob wanted blood. I was pretty angry, and a bit of a wild man at that age, so after firing a couple of shots in the air, I tossed the machete onto the seat beside me, stuck the pistol in my belt, then quickly collared two rabble-rousers (as a Game Warden I had the rights to search, seize and arrest) and hurled them into the back of the vehicle. The people in front had to either scatter or get run down, but about 50 screaming men and boys chased after my vehicle, throwing stones and waving knives, machetes and sticks.

Why the fuss? I couldn't think of anything I'd done or said to get them so enraged, but I was a foreigner and all foreigners were suspect during that nervous time. I drove the captives to a hospital, had them checked out so they couldn't later claim I had run them down or something. Getting money out of scared foreigners that way was a minor industry back then in Addis Ababa.

If that wasn't enough, a friend from the Israeli embassy later told me that I was marked for assassination. An attempt had already been made on my life in Gondar, the old castled city and provincial capital of Begemdir, where I sent off reports to the capital and picked up supplies and wages for park staff and workers.

One night, walking back to my hotel from a bar along an unlit, deserted lane, two men came at me from behind wielding iron-tipped clubs. Thanks to my karate skills I was able to fight it out without drawing my pistol. After the skirmish I returned to my hotel to bandage up the wounds on my hand and forearm. The next morning, as I was having breakfast and getting ready to return to the park, a student I was friendly with came to the hotel and told me that, just after the fight, a police Land Rover drove up the lane with its lights out and officers dragged the two attackers I had left lying on the ground to the vehicle, tossed them into the back, and drove off. Later, other witnesses told me the police had driven the men beyond the city limits and dumped them in a field outside the local slaughterhouse, a place that attracted hungry hyenas.

On my next visit to Gondar, when I made inquiries to the police about the incident they claimed to have known nothing. This was not surprising, as the Chief of Police was involved in the illegal wild-animal fur trade, which we had been disrupting. That unsavory gentleman had already warned me to stay away from fur traders. I told him that as I was a Game Warden, it was my job not only to protect the park but also to find and arrest such criminals.

When I got back to Gondar from Addis Ababa after the park boundary meetings there were riots there too. A police Land Rover had been burned. Police with guns faced the students. At night, they dragged students out of their houses and beat them with clubs while their parents watched and pleaded for them. A couple of bright young men whom I knew vanished.

Then there were the anti-Arab riots.

The Eritrean Liberation Front had been blowing up planes and generally making a nuisance of themselves, and there had been reports in the press about links with Syria. A huge "spontaneous" anti-Arab parade was held in Addis Ababa, with Amhara warriors wearing their lion-mane headdresses, carrying round shields and curved scimitars. In cities and villages all over Ethiopia, Arabs were beaten up and their shops were stoned or even looted.

At that time, several cultured Ethiopians came to me, asking if I could get guns and ammunition for them. (Of course I could, but would not.)

I cannot imagine now, in 2010, that Ethiopians have changed so much that they will stay subdued and silent while being displaced from their land by foreign investors. I especially fear that the Amhara, who are Coptic Christians, will be incensed if Arab Muslims are involved in any moves to take away their land rights. The Amhara are an especially proud and ancient people. It was ordinary Ethiopians, many of them barefooted and lightly armed, who finally drove out the Italian invaders in 1941, despite their machine guns, howitzers, planes and tanks.

Nothing I can do or say will change any of this, but even so I, with deep respect for Ethiopians — and as a citizen of this country — urge Japan not to join in this greedy scrabble. We have far too much arable land going to waste here in Japan. Land and food is not only a question of money. People who live off their land feel deeply about it, no matter how poor and defenceless they may seem.

Japan should shun this new kind of colonization like a plague, no matter what well-paid city-based officials may say. As other people who have lived and worked in the country have noted, I can myself affirm a strong belief that there is no land in Ethiopia that has no owners or users.

Back in the late 1960s, we had enough problems establishing a national park, one in which farmers were allowed to keep on using their land. We tried to stop poachers and illegal loggers, and that was not easy. I doubt if we would have survived if we had tried to take the locals' land from them — even if it was for reasons of wildlife protection or water conservation.

Japan, please, by all means help poor African farmers — but do not have anything to do with displacing them!