Korea Herald | 24 March 2011

Alarmed over a surge in global food inflation, Korea is ratcheting up its efforts to safeguard against price volatility and secure a stable supply.

The government and companies are joining hands to expand the country’s overseas farming bases, establish a direct import channel and modernize agricultural production and distribution.

Fear about a food crisis has gripped the world in recent years as exploding demand, bad weather and speculative commodity investments combined to lift grain prices.

Among the countries hit was Korea, one of the world’s largest importers of agricultural produce. The country’s food supply has been further dampened by its worst outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease.

Food inflation poses a grave challenge to President Lee Myung-bak ahead of next year’s presidential and parliamentary elections. It is threatening to undercut his priority of stabilizing the livelihood of low-income citizens and limiting policy tools for keeping post-crisis economic recovery sustainable.

“Without actions taken, there is a possibility that Korea will face a serious supply crunch within two or three years,” said Lee Cherl-ho, a Korea University food bioscience professor who chairs the Korea Food Security Research Foundation

“Food security is an extremely urgent issue. It’s very important to have a distribution structure at home and abroad.”

The government has recently advanced its plan to operate a grain trading firm in Chicago for direct importation and is expediting work to expand domestic grain stocks and boost investment in overseas farmland.

Experts call for bolder, better-informed strategies, increased funding and closer public-private sector cooperation, in order to cope with the cutthroat competition among countries to secure agricultural land and the global dominance by a few multinational behemoths.

Heavy reliance on imports

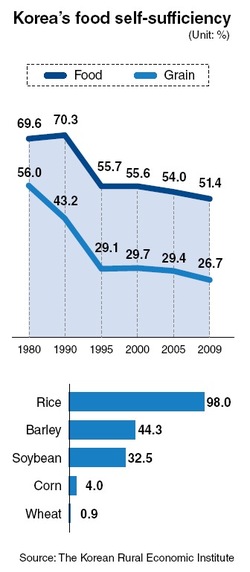

Korea imports a majority of key grain products except rice. As of 2009, its self-sufficiency rates for wheat, corn and soybeans were 0.5 percent, 1 percent and 8.4 percent, respectively, government data showed.

The figure for grain in general currently stands at a mere 26.7 percent. In stark contrast, nations such as the U.S., China and Germany have kept their rates at around or greater than 100 percent ― Korea ranks near the bottom among OECD nations.

The most urgent task, experts agree, is an early establishment of a stable international procurement system.

“We don’t have a large import company like the U.S., which already took over the grain futures markets, and our middle agents are mostly Japanese. We can’t even buy our food by ourselves,” Lee said.

Last year’s grain imports reached 14.2 million tons ― corn with 9 million tons, wheat 3.7 million tons and soybeans 1.5 million tons ― all from major agro-food groups that reign over the market oligopoly.

Cargill and ADM account for nearly half of Korea’s imports of corn, wheat and soybeans, according to Samsung Economic Research Institute. The ratio goes beyond 70 percent if combined with Bunge, France’s Louis Dreyfus SAS and Japanese traders such as Marubeni Corp. and Mitsubishi Corp.

The limited range of dealers, coupled with heavy dependence on imports, further exposes the country to international price volatility.

“We’ve been witnessing serious price fluctuations of grain in the local market when dealing with foreign major companies due to the involvement of speculators,” an official at the Ministry for Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries said.

Farm trading scheme

The state-run Korea Agro-Fisheries Trade Corp. (aT) is set to open an agricultural trading firm in Chicago on March 31 in cooperation with Samsung C&T, CJ CheilJedang Corp., STX Corp. and Hanjin Transportation Co., Ltd.

The establishment, expected in May, has been pushed forward amid global instability and mounting public anxiety over inflation.

Under the public-private partnership, aT plans to invest 20 billion won ($17.8 million) and the four firms together will pump 25 billion won into the project this year, officials said.

The project is aimed at supplying up to 30 percent of Korea’s grain needs, or 4 million tons, by gradually raising the amount of dealings over a 10-year period through 2020.

The total budget is estimated at about 240 billion won, of which 95 billion won will come from aT.

The operators plan to import 5 million tons of corn and soybeans each and purchase a grain elevator at a U.S. production site this year.

The envisioned company was initially known to focus on directly purchasing from local farmers. But it will instead work with a wide range of suppliers including global grain giants, an official told The Korea Herald.

“Previous news reports said the scheme would exclude the major grain companies but it is not true.” the source said. “We are completely open to all potential partners including Cargill, Inc., Archer Daniels Midland and Bunge Ltd. of the U.S.”

A team of 10 or more professionals ― two from each firm and other experts ― will work to build a distribution network, he added.

It would help Korea improve its grain self-sufficiency and better handle speculative attacks in futures markets, experts said.

“It’s the road Korea should take before it’s too late,” said Kim Yong-taek, senior research director at the state-run Korean Rural Economic Institute.

“We have long lacked a control system for agricultural commodities. Despite tough conditions surrounding the issue, it’s a timely decision given the necessity and a global trend.”

Even with the grain trading house, Korea would still face daunting challenges in finding suppliers in the tight global market, experts said.

“They’ve been controlling the whole gamut from production to sales for so long,” said Park Hwan-il, a research fellow at SERI. “It is extremely difficult for newcomers to start from zero when others operate based on their more than 100 years of know-how.”

Such a large-scale business requires extensive knowledge and experiences not in just agriculture and trade but in areas like freight, finance and meteorology, he noted.

“It’s not just that you buy stuff and ship it,” Park said. “It takes a lot of time, money, information and overseas networking to establish a distribution channel. We don’t even have trade specialists who have the comprehensive perspective needed to read the trend in the global grain market.”

Fight for land

Breaching the market is yet possible, experts said, if Korea makes long-term, consistent efforts.

“It will have to target untapped suppliers who aren’t bound by contract with the agro-food giants, though they’re not easy to find,” Park said.

Kim of the KREI also stressed the need for thorough strategies to work out the project.

“It’s a very risky business,” he said. “We can’t afford a big mistake given the huge investment of taxpayers’ money and difficulties they are now faced with.”

As part of its commitment to reinforcing food supply, the government said early this year it was considering expanding public reserves by adding key crops like soybeans, corn, wheat and barley to the mandatory list.

Under the law that took effect in 2005, it must store 864,000 tons of rice in its warehouse at all times by way of precaution against a war or natural disasters.

If expanded, the government could reserve the amount of each crop that Koreans consume for a month or so, starting in the latter half of the year after setting up necessary policies and securing budgets, the Ministry for Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries said.

The ministry also announced early this month that it plans to allocate 30 billion won to help local firms obtain overseas farmland this year and 10 billion won to sponsor foreign governments that support such investments.

“Private companies will be in charge of investment, while the government and state-run corporations like the Korea Rural Community Corp. give technical support,” a ministry official said.

Korea’s low food self-sufficiency correlates with the size of farmland available in the country. Its cultivated land per capita is 0.04 hectare, KREI figures show, which is tiny compared with other industrialized countries ― the U.S. comes in at 1.5 hectare, France 0.5 hectare and the U.K. 0.3 hectare.

Seoul has been promoting overseas agricultural development since 2008. Currently 60 companies are operating farms in 16 countries ― mostly in eastern Russia, and others in Southeast Asian nations and Brazil.

As of 2010, they own 240,000 hectares of land collectively, equivalent to about 14 percent of the country’s total farmland, yielding 87,000 tons of grain annually, the ministry reported.

Among the developers, Hyundai Heavy Industries acquired a 67.6-percent stake in Khorol Zerno LLC in 2009, which operates a 10,000-hectare farm near Vladivostok, Russia.

It harvested 4,500 tons of beans and 2,000 tons of corn in 2009, company officials said.

The world’s largest shipbuilder said it plans to add more land, reaching a total of 50,000 hectares by 2012, targeting to produce more than 100,000 tons of beans and corns a year by 2015.

“(The farm) sits on one of the best agricultural regions in Russia because it’s easy to secure ample farmland and skilled farmers with relatively low investment,” a company official said.

“Overseas farm development is a win-win project for both countries because it can help Korea ease the chronic supply shortages and price fluctuations, while creating jobs and improving agricultural productivity in Russia.”

In 2008, a local startup established an agricultural firm called KomerCN in Kampong Speu, southwestern Cambodia, and started growing corn on a 13,000-hectare site.

Chungnam Global Agriculture Resource Development also formed a guild with about 1,400 local farmers and purchases all of their produce to bring back into Korea.

The annual output ― from the firm and guild members combined ― comes in at 850,000 tons, which equals about 10 percent of the country’s corn demand, according to company officials.

KomerCN plans to ship the crops to Daesang Corp., Korea’s leading food business. The two firms said early this month they began field research there before striking an official procurement deal.

“It’s the fruit of our efforts for the past two and a half years since we moved into Cambodia in 2008 with support from the Agriculture Ministry and South Chungcheong provincial government,” said Lee Woo-chang, the firm’s president.

On top of such aids, Lee at Korea University emphasized the need for nurturing local agriculture and food industries.

“We should foster the food industry to strengthen its role in food security,” he said, adding that it accounts for nearly 40 percent of the country’s food imports.

“Large firms like Nestlé of Switzerland have a capability to obtain food nearly whenever it needs to. The country can benefit from that when an emergency comes.”

By Shin Hyon-hee ([email protected])