Research published by alternative investment manager Aquila Capital in December 2013 showed that 23% of institutional investors are looking to increase their exposure to farmland over the next 12 months and 11.4% are planning to increase it over the next five years.

Farmland: Yield-starved investors go back to the land

by Louise Bowman

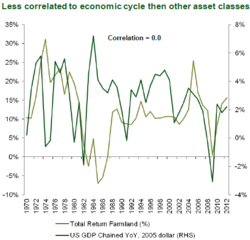

Plenty of room for growth in neglected asset class; Good inflation hedge relatively uncorrelated to economic cycle

Last year many yield-hungry institutional investors stretched their mandates to incorporate alternative assets such as infrastructure, real estate and direct lending. This year could be the one in which they focus on one of the least-developed asset classes available: farmland. Research published by alternative investment manager Aquila Capital in December showed that 23% of institutional investors are looking to increase their exposure to farmland over the next 12 months and 11.4% are planning to increase it over the next five years. Aquila manages a specialist fund investing in milk production in Australia.

The asset manager polled 71 institutional investors based in the UK and Europe in October last year. Buyers are looking to get into an asset class that still accounts for only 1.3% of investment portfolios and in which only 17% of investors have an allocation at all, so there is plenty of room for growth.

This year could, therefore, see a surge in interest in farmland from investors with very little experience in this complicated asset class. “This is such a nascent asset class for institutions and when you look at institutional managers there is no real track record of exiting assets. Yet the potential returns hold up well against other alternative asset classes when compared on an unlevered basis,” says Tim Hornibrook, executive director of global agriculture at Macquarie Agricultural Fund Management, which has managed farmland assets since 2003 and run an institutional fund since 2007.

The study concluded that climate change and depletion of agricultural land are the most important factors driving investment returns from farmland. Farmland investing has similar characteristics to asset classes such as real estate or infrastructure, but also important differences. It is a good hedge against inflation and is far less correlated to the economic cycle than sectors such as timber or commercial property. Unlike real estate or infrastructure, farmland does not have a specific useful life: where investing in real estate involves dealing with a depreciating asset, with agriculture the asset (the land) is appreciating. But, like infrastructure, agricultural investments can be highly illiquid. One of the world’s largest grain producers, El Tejar, has struggled to achieve an IPO or a public bond issue in recent years. Founded in Argentina, it is 40% owned by London-based hedge fund Altima Partners, with US private equity investor Capital Group holding 15%. Last year the firm shifted strategy from leasing to owning farmland in response to soaring rental prices in Argentina and has now moved its headquarters to Brazil.

Limited exposure to the economic cycle

According to the Aquila data the most popular method by which investors have gained access to farmland are specialist investment funds (53%) and closed-end funds (40%), but it is noteworthy that 57% of investors declared themselves disappointed with the performance of closed-end funds and 42% were disappointed with specialist investment funds. So although the asset class might be the new frontier in the chase for yield, it should be approached with caution.

“The reasons for investing in farmland are demand and supply projections for agricultural commodities,” explains Reza Vishkai, head of specialist investments at Insight Investment, whose farmland fund achieved first close in August 2011. Investments have so far focused on livestock in Australia, dairy in New Zealand and cropping in Romania. “Demand for agricultural commodities will expand until 2050 when population growth is expected to peak. Supply growth is slowing due to climate change, water shortages, land degradation and the fact that much of the potential gains from intensive farming have already been realized. The fixed supply of high quality land able to meet the increasing demand means that owning farmland in the right places will be a very attractive investment.”

Institutional investors overwhelmingly agree that further private investment in agriculture is required to meet the global demand for food, but not on how to best exploit the situation. There are probably only around 12 credible players in the market worldwide – most of which are funds. For example, the Hancock Agricultural Investment Group manages $1.8 billion of agricultural real estate exposure and UBS Agrivest invests in US farmland as part of its real estate exposure. Seventy percent of investors in the survey cited backing companies that provide farm supplies as an attractive opportunity while 50% believe that owning and developing farms – akin to a private equity-style approach – also provides strong returns. “There are two ways to approach farmland: invest in funds that seek to create value by operating and enhancing the asset before exiting and realizing value or directly buy the land and lease it out, which is attractive to very large investors with very long time horizons,” explains Vishkai. TIAA-Cref, which has farmland holdings of more than $4 billion, launched TIAA-Cref Global Agriculture in May 2012, additionally backed by a number of pension funds, with $2 billion permanent capital to invest directly in row crops and permanent crops. According to Macquarie the total value of farmland globally is $8.4 trillion, but just $30 billion to $50 billion has been institutionally invested in farmland globally – one-third in funds, with the rest taking the form of direct investment.

Despite this enormous opportunity gap investors could find a move into farmland tougher than it looks. “This is a very difficult asset class to access as it is essentially a private market – the listed farmland sector is so small and typically trades at a discount to NAV,” says Hornibrook. “There are 200 managers trying to raise money on the private side but few will be successful – no-one has a recognized institutional track record so it is difficult to raise capital and you have to wonder whether by the time the sector has established an institutionally recognized track record whether the same level of returns will be possible. Given the lack of track record, the due diligence required on the asset manager is similar to that for a boutique equity asset manager start-up.”

Vishkai at Insight emphasizes the need for the right people to be on board. “Investing in agriculture is hard – it is difficult to get people with the right combination of skills.” Even if investors can get comfortable with a manager, this is often a tricky asset class to mesh with a wider asset allocation. “One challenge is determining which investment bucket this fits into,” Hornibrook tells Euromoney. “This can fit into a real assets bucket, a commodities sleeve, private market sleeve or a private equity bucket. This is a boon but it is also a negative – if an asset fits into too many buckets it can also fit into none.

“This is a very complex, political and emotive asset class,” he continues. “It is one where you are far more likely to see government interference.” A recent example of this was Brazil, which in 2010 banned foreign ownership of land, stalling huge volumes of international investment targeted at its agriculture sector (see Euromoney January 2014, Land rush on Brazil's frontier).

Macquarie manages a pastoral fund in Australia and cropping funds in Australia and Brazil. It has focused its efforts in Australia on aggregating farms under a collective umbrella in order to benefit from economies of scale. As such they are building the business from the ground up rather than running a series of discrete assets, as would be the case with infrastructure or private equity. The options for exit from such a strategy are limited to an IPO or trade sale and it requires a level of experience in the asset class that few looking to enter it will have. “There are more and more investors that just due to their sheer size will find farmland difficult to access,” warns Hornibrook. “It is a long and painful exercise to aggregate farms into a portfolio size that is meaningful to a large institution. It is the most fragmented sector in the world and is inefficient and starved of capital. But as food prices rise value has to go back to the farmer in order to send the appropriate signals to increase production – that is why we invest in primary production.”

For those with the stomach and experience for it, direct investment in farmland could become increasingly popular as a comparatively lucrative alternative asset allocation. TIAA-Cref Global Agriculture has targeted annual returns of 8% to 12% for a projected 21-year investment timespan. “Farmland investing is quite inefficient and there is the ability to create value,” says Vishkai. “It should be an active investment because much of the return you create can be within your control.”