Investment and Pensions Europe | February 2014

Sustainability is key in farmland

By Nina Röhrbein

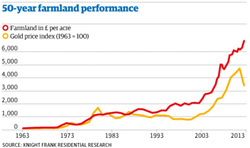

According to a recent survey by alternative investment fund manager Aquila Capital, 23% of the 71 institutional investors surveyed are looking to increase their exposure to farmland in 2014, while a further 74% will maintain their investment at its current level.

No wonder, given that the Australasian farmland holdings of Sweden’s AP1 returned 20.7% over 2012.

But despite interest from some large institutions, farmland currently represents only 1.3% of their portfolios, according to the survey,

Negative headlines surrounding land grabbing, destruction of local food production and environmental degradation have not helped attract pension funds to the asset class, particularly in Africa and other emerging and frontier markets.

“Land grabbing is of course a big issue in developing countries where thousands of families are being displaced,” says Arvind Narula, CEO of the Thai organic rice company Urmatt, which operates a contract farming operation. “There are alternative, lower capital cost and kinder solutions with high returns. Out-grower [contracted farming] projects that are well thought out, well-manned with the correct expertise and technical know-how in crops for which demand exceeds supply can be very rewarding for all players.”

To avoid negative headlines, institutional investors need to find credible partners in the market by looking at their experience, track record and familiarity with local circumstances, according to Tanja Havemann, director and founder of the sustainable investment adviser Clarmondial. “Few funds exist with a good track record, so thorough due diligence is crucial,” she says.

And it is often this lack of track record that is deterring investors, as is a lack of knowledge and understanding, according to half of Aquila’s respondents.

“The problem with the asset class is that farming is intuitively perceived to be a romantic, easy-to-understand business – but in reality there are lots of variables which can only be successfully dealt with by practitioners with in-depth education and experience,” says Detlef Schoen, group head of farm investments at Aquila Capital, who says the restricting factors are the lack of good operators and the lack of capital, which is exacerbated by impending generation change. “In addition, foreign land ownership – critical to a business model based on capital protection – is prohibited in certain countries such as Canada, Russia or Ukraine, while it is restricted in others, like Brazil.”

Tim Hornibrook, executive director at Macquarie Agricultural Funds Management, Macquarie Infrastructure and Real Assets, recommends investors diversify geographically and climatically to reduce the weather risk, while taking into account their appetite for sovereign risk.

He says investors should look at whether a country is agronomically appropriate – in other words, does it have the right mix of weather, soils and access to water. Other things to consider are whether a country is a net exporter or importer of food, whether it has a variety of input supplies, a choice of buyers, and access to infrastructure.

A balance has to be struck between sovereign and agronomic risk. A food-insecure country with lots of smallholders, for example, can have a higher potential for social unrest.

“Husbandry of the resources – sustainability in its original sense – is extremely important, as depletion of the soil leads to short-term returns,” says Schoen.

From a sustainability perspective, it is perceived to be easier for institutional investors to invest in established agricultural markets in investment-grade countries, such as Australia, New Zealand and the US.

AP2, for example, only invests in large-scale agriculture real estate in countries with a clearly defined legal structure. It currently invests in Australia, Brazil and the US. To undertake the investments in all three countries, the fund set up a joint venture with US financial organisation TIAA-CREF.

“To make sure our investments are sustainable, we have to undertake in-depth due diligence to ensure the companies that we select share our values,” says Christina Olivecrona, sustainability analyst at AP2 whose farmland investments make up 1% of its overall SEK248.3bn (€28bn) investment portfolio. “TIAA-CREF was a good match for us in that respect.”

Alongside five other funds from Denmark, the Netherlands and the UK, AP2 and TIAA-CREF in 2011 developed the Principles for Responsible Investment in Farmland to promote best practice in environmental sustainability, labour and human rights, existing land/resource rights and business standards.

AP2, which says it benefited from its experience with forestry when it began investing in farmland, sends out an annual survey to check how its external managers have implemented the farmland principles, while TIAA CREF also has a standalone report on its overall investments in agriculture.

But farmland sustainability factors are often subjective, according to Havemann at Clarmondial. For some the important factor may be the creation of jobs, while for others it is the improvement of agricultural practices, such as the planting of trees alongside fields or organic certification.

“Unfortunately, there is not yet much consensus around a common reporting method,” she says, even though many private equity firms are already looking at social metrics. “A lot of the private equity funds are quite cagey about their information and the issue of land grabs has probably made them even more reluctant. The problem has been a lack of transparency from all sides about what is actually happening on the ground.”

However, Havemann does not think that all the criticism of farmland investment has been warranted. She believes that fund managers and investors can avoid negative headlines through transparency and positive engagement.

But Narula at Urmatt believes that investors need go one step further.

“They have to look at investments in agriculture in communities that need developmental help,” he says. “They need to create a mutually beneficial investment that provides good returns while positively impacting these communities and invest in crops that have a clear marketability, not agricultural products that will require chasing scarce markets or face strong competition. Selecting the wrong crops to fund hurts both the investor and the communities where the investment is made. There have been too many investments in projects that have failed because the choice of products was wrong.”

For Narula, the optimal investment category is specialised agriculture where there is long-term unmet demand such as seaweed extract carrageen, sandalwood for perfume extraction and protein extracted from peas.

The underlying story, of course, is that agriculture produces an essential item – food.

“There is a renaissance going on at the moment because we are shifting from a chronically oversupplied scenario, which we saw through the late 1990s and early 2000s in Europe, Russia and the US, to a structural deficit driven by growing demand and changing diets in the developing economies,” says Schoen.

And with this growing theme, money can be made.

Sustainability is key in farmland

By Nina Röhrbein

According to a recent survey by alternative investment fund manager Aquila Capital, 23% of the 71 institutional investors surveyed are looking to increase their exposure to farmland in 2014, while a further 74% will maintain their investment at its current level.

No wonder, given that the Australasian farmland holdings of Sweden’s AP1 returned 20.7% over 2012.

But despite interest from some large institutions, farmland currently represents only 1.3% of their portfolios, according to the survey,

Negative headlines surrounding land grabbing, destruction of local food production and environmental degradation have not helped attract pension funds to the asset class, particularly in Africa and other emerging and frontier markets.

“Land grabbing is of course a big issue in developing countries where thousands of families are being displaced,” says Arvind Narula, CEO of the Thai organic rice company Urmatt, which operates a contract farming operation. “There are alternative, lower capital cost and kinder solutions with high returns. Out-grower [contracted farming] projects that are well thought out, well-manned with the correct expertise and technical know-how in crops for which demand exceeds supply can be very rewarding for all players.”

To avoid negative headlines, institutional investors need to find credible partners in the market by looking at their experience, track record and familiarity with local circumstances, according to Tanja Havemann, director and founder of the sustainable investment adviser Clarmondial. “Few funds exist with a good track record, so thorough due diligence is crucial,” she says.

And it is often this lack of track record that is deterring investors, as is a lack of knowledge and understanding, according to half of Aquila’s respondents.

“The problem with the asset class is that farming is intuitively perceived to be a romantic, easy-to-understand business – but in reality there are lots of variables which can only be successfully dealt with by practitioners with in-depth education and experience,” says Detlef Schoen, group head of farm investments at Aquila Capital, who says the restricting factors are the lack of good operators and the lack of capital, which is exacerbated by impending generation change. “In addition, foreign land ownership – critical to a business model based on capital protection – is prohibited in certain countries such as Canada, Russia or Ukraine, while it is restricted in others, like Brazil.”

Tim Hornibrook, executive director at Macquarie Agricultural Funds Management, Macquarie Infrastructure and Real Assets, recommends investors diversify geographically and climatically to reduce the weather risk, while taking into account their appetite for sovereign risk.

He says investors should look at whether a country is agronomically appropriate – in other words, does it have the right mix of weather, soils and access to water. Other things to consider are whether a country is a net exporter or importer of food, whether it has a variety of input supplies, a choice of buyers, and access to infrastructure.

A balance has to be struck between sovereign and agronomic risk. A food-insecure country with lots of smallholders, for example, can have a higher potential for social unrest.

“Husbandry of the resources – sustainability in its original sense – is extremely important, as depletion of the soil leads to short-term returns,” says Schoen.

From a sustainability perspective, it is perceived to be easier for institutional investors to invest in established agricultural markets in investment-grade countries, such as Australia, New Zealand and the US.

AP2, for example, only invests in large-scale agriculture real estate in countries with a clearly defined legal structure. It currently invests in Australia, Brazil and the US. To undertake the investments in all three countries, the fund set up a joint venture with US financial organisation TIAA-CREF.

“To make sure our investments are sustainable, we have to undertake in-depth due diligence to ensure the companies that we select share our values,” says Christina Olivecrona, sustainability analyst at AP2 whose farmland investments make up 1% of its overall SEK248.3bn (€28bn) investment portfolio. “TIAA-CREF was a good match for us in that respect.”

Alongside five other funds from Denmark, the Netherlands and the UK, AP2 and TIAA-CREF in 2011 developed the Principles for Responsible Investment in Farmland to promote best practice in environmental sustainability, labour and human rights, existing land/resource rights and business standards.

AP2, which says it benefited from its experience with forestry when it began investing in farmland, sends out an annual survey to check how its external managers have implemented the farmland principles, while TIAA CREF also has a standalone report on its overall investments in agriculture.

But farmland sustainability factors are often subjective, according to Havemann at Clarmondial. For some the important factor may be the creation of jobs, while for others it is the improvement of agricultural practices, such as the planting of trees alongside fields or organic certification.

“Unfortunately, there is not yet much consensus around a common reporting method,” she says, even though many private equity firms are already looking at social metrics. “A lot of the private equity funds are quite cagey about their information and the issue of land grabs has probably made them even more reluctant. The problem has been a lack of transparency from all sides about what is actually happening on the ground.”

However, Havemann does not think that all the criticism of farmland investment has been warranted. She believes that fund managers and investors can avoid negative headlines through transparency and positive engagement.

But Narula at Urmatt believes that investors need go one step further.

“They have to look at investments in agriculture in communities that need developmental help,” he says. “They need to create a mutually beneficial investment that provides good returns while positively impacting these communities and invest in crops that have a clear marketability, not agricultural products that will require chasing scarce markets or face strong competition. Selecting the wrong crops to fund hurts both the investor and the communities where the investment is made. There have been too many investments in projects that have failed because the choice of products was wrong.”

For Narula, the optimal investment category is specialised agriculture where there is long-term unmet demand such as seaweed extract carrageen, sandalwood for perfume extraction and protein extracted from peas.

The underlying story, of course, is that agriculture produces an essential item – food.

“There is a renaissance going on at the moment because we are shifting from a chronically oversupplied scenario, which we saw through the late 1990s and early 2000s in Europe, Russia and the US, to a structural deficit driven by growing demand and changing diets in the developing economies,” says Schoen.

And with this growing theme, money can be made.