From WRM's Bulletin 224

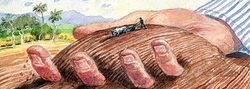

(1) Current land grabbing practices include the capture of control of relatively vast tracts of land through a variety of mechanisms. In the process, land use acquires an extractive character, irrespective of whether the land grab is motivated by international or domestic (food security) pressures, capital investors searching for new investments with quick returns, climate change policies or other purposes. For indigenous peoples and traditional and peasant communities for whom the land and forests provide a livelihood, such large-scale land grabs result in a loss of control or access to food, water, medicines, shelter and many other local forest and land uses. This loss of control or access jeopardizes and often destroys community livelihoods, cultures and/or their autonomy as traditional or indigenous peoples. Land grabs imply direct and/or indirect violence towards local populations opposing the inevitable loss of land and forests such large-scale land grabs involve.

The study “Land grabbing and human rights: The involvement of European corporate and financial entities in land grabbing outside the European Union”, prepared for the European Parliament subcommittee on Human Rights, analyses the global land rush within a human rights framework. The study examines the implications of particular land deals involving European Union-based investors and their impact on communities living in areas where the investments are taking place.

The study also looks at the role of the state in creating, in cooperation with corporations and international development agencies, the impression that land use and property regimes on the lands targeted for land grabs are inefficient, destructive, or both. Thus, territories used by peasants engaging in shifting cultivation and small-scale agriculture, pastoralists, artisanal fisherfolk, and forest peoples relying on forests for their livelihoods are most often targeted by such large-scale land grabs.

European Union actors and key land grabbing mechanisms

European Union (EU) corporate and financial entities involved in land grabbing may be implicated in a variety of human rights abuses. Actors – financial and corporate, private and public – involved in land grabs are linked to each other and to the EU in different ways. It is important to understand the main tactics used by these entities for grabbing land:

How EU-based private companies assume control over land

A company that has its headquarters or substantial business activity in an EU member state can be involved in a land deal at different points of the investment web. It can be a financial institution or company that provided a loan or acquired shares in a land deal. It might be a company that is involved in the implementation of a given project (coordinating or exercising), or a main client of the produced goods. In some cases, the operations on the ground are managed and/or carried out by a locally registered company, usually a subsidiary of the EU-based company (the subsidiary may have other shareholders), but business operations are coordinated from the company’s headquarter or parent company. The land may have been acquired by the local company or by the EU-based company through purchase, lease or concession. The EU-based company may benefit from support by its home country, through intervention by the embassy or via financial or technical support from development agencies for the land acquisition.

The case of Luxembourg-based company Socfin

Socfin (Société Financière des Caoutchoucs), with the French group Bolloré as main shareholder, is an agro-industrial group specialized in oil palm and rubber plantations. The Socfin group is a very complex web of cross investments and shareholdings. Financial holdings of the group are based in Luxemburg; operational companies are based in Luxemburg, Belgium and Switzerland; and subsidiaries for the management of the plantations are established in a dozen Sub-Saharan and Southeast Asian countries. Although Socfin is a very old company with operations dating back to the colonial Belgian rule in what was called Belgian Congo, the company has gone through a significant expansion of its operations in recent years, benefiting from the growing world demand of palm oil for industrial food and agrofuels. Socfin largely relies on self-financing and commercial loans for the expansion of its operations, although it has on several occasions benefited from financial and technical support of Development Financial Institutions like the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank Group or the German Investment Corporation, DEG. Severe environmental, social and human rights impacts of Socfin’s land investments have been denounced. In different countries this has led to land conflicts, social unrest and criminalisation of local leaders (See recent Action Alert).

Finance capital companies from the EU involved in land grabbing:

Finance capital companies include institutions as diverse as banks, brokerage companies, insurance firms, financial service providers, pension funds, investment funds and firms and venture capital funds (investments in high risk businesses). Finance capital companies have been increasingly involved in land deals since the beginning of the financial crisis and the food price spike in 2007-2008. Since then, land became a target for financial capital investors who needed to find new opportunities for creating quick returns on investment or to find a safe investment for money that could not be invested elsewhere in more lucrative ways. This trend is increasing the importance of financial markets, financial motives, financial institutions and financial elites in the land acquisitions. Financial actors may not always be very visible in a land deal, as they may be financing land grabs indirectly: Banks may provide credit to companies involved in land deals, or pension funds or private and corporate investors might be part of an investment fund that does not disclose where its investments come from.

Land grabbing via public-private partnerships:

In public–private partnerships (PPPs), public funding is used to reduce investment risk for or facilitate investment of private sector, usually corporate players. The partnership can involve one or more governments and one or more private sector companies. In the context of large-scale land deals, the public sector ensures an environment that facilitates land acquisitions and subsequent business activities by private corporations through specific policy interventions. PPPs blur the lines between public and private actors and mix up their respective roles and responsibilities and they thus carry the risk that the state abdicates its public responsibilities and obligations. Indeed, PPPs allow corporations to evade many risks involved in investments in land when governments lower investment risks or twist rules and regulations to their advantage.

The Chad-Cameroon pipeline

Initiated in 2000 to transport the crude oil produced in southern Chad to the Atlantic coast of Cameroon, the 1,000 km pipeline is one of Africa’s largest public-private partnerships. Project ownership is comprised of a three-company oil consortium (Exxon/Mobil 40%, Petronas Malaysia 35% and Chevron US 25%) and the governments of Chad and Cameroon, which hold a combined 3% stake in the pipeline portion of the project. The funds used to secure the investment share of the two countries were provided in the form of a loan by the World Bank (2). As Samuel Nguiffo, from CED-AT Cameroon, argues in his article re-printed in this bulletin (“Infrastructure, development and natural resources in Africa: A few examples from Cameroon”), it is clear that the governments incur debt, and those who benefit are the multinational corporations.

EU Development Finance involved in land grabbing:

Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) are important actors in land grabbing, namely as enablers of land deals and investment projects. DFIs are specialised development banks that are usually majority owned by national governments and contribute to the implementation of the latter’s foreign development and cooperation policy. However, information on the activities of DFIs is not always easily available. DFIs largely invest money they raise on capital markets; some may source additional capital from national or international development budgets. The scale of private sector financing from International Finance Institutions (IFIs) and European DFIs has increased dramatically. In some cases, involvement of different DFIs can result in the majority of a company’s shares being in the hands of DFIs.

Feronia’s oil palm plantations in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Feronia Inc., a company listed on the Toronto stock exchange, operates industrial oil palm plantations in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In January 2016, Feronia became majority owned by CDC, the UK’s Development Finance Institution, and several other European development banks, through their investments in the African Agricultural Fund. This Fund is a Mauritius-based private equity fund financed by bilateral and multilateral African development finance institutions. Its Technical Assistance Facility (TAF) is funded primarily by “the European Commission and managed by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The TAF is co-sponsored by the Italian Development Corporation, United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO) and the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA)”. In addition, development banks from Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands are also involved as investors. See article in this bulletin: “DRC: Communities mobilise to free themselves from a hundred years of colonial oil palm plantations”.

Land grabbing through EU policies:

The following EU policies are particularly relevant to the context of land grabbing:

Investment policies:

The current international investment regime as promoted by the EU and EU member states contributes, among other serious human rights violations, to an enabling international environment for land grabbing. Investment treaties are by nature one-sided and only investors can invoke the treaty protections and put claims forward against states, even suing them.

Development policies:

In recent years, the EU has increasingly shifted towards a private sector-led approach to development, arguing that private sector engagement and funding is an indispensable complement to EU development assistance.

Bioenergy policies and the EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED):

The RED was adopted in 2009 and entered into force in 2010, and aims at reducing greenhouse gas emissions through the significant scaling up of forms of energy classed as renewable, including agrofuels and production of energy from burning wood. Civil society organisations have repeatedly pointed to the direct link between land grabbing and documented the human rights abuses and the EU agrofuels and bioenergy policies, as well as the involvement of European companies as important actors in land grabbing in this context. (3)

Trade policies:

With regard to land grabbing, a central concern relates to the incentives created through EU trade agreements for large-scale land acquisitions in countries outside the EU to produce crops for the EU market.

Climate policies, agreements and treaties:

Agreements made at the United Nations Convention on Climate Change and related events have direct effects on national legislation. Many industrialized governments and multilateral agencies have started programmes and funds to jump-start carbon markets in the countries of the global South, especially those with tropical forests. Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative, for example, which is pushing for the implementation of REDD+ programmes in the Congo Basin region, the German and French governments as well as the World Bank are some of the relevant players. Large-scale REDD+ projects are being planned in the Republic of Congo and in the DRC, with serious concerns over the lack of adequate consultations with local communities and both apparently might actually end up dispossessing these peoples even further. See article in this bulletin: “Protected Areas in the Congo Basin: Failing both people and biodiversity”.

Land grabbing through forest conversion:

Converting forests to other land uses that serve corporate interests is another way of land grabbing. In the last decade, the Congo Basin has experienced an unprecedented growth in demand for land to develop large-scale commodity plantations, particularly of crops such as palm oil. This demand is continuing at a rapid rate. A substantial proportion of land allocated for large-scale agriculture production in the region, particularly for oil palm, is being deforested. Oil palm plantation companies are targeting forests also to generate profits from the timber they can sell, further threatening tropical forests and forest-dependant populations. On top of this, the on-going forest conversion is exacerbating regional deforestation rates and is highly correlated with land rights abuses and a range of other social impacts (4). As a result of these new developments, in 2013, industrial agro-conversion may already have become the largest driver of deforestation in the Congo Basin (5).

Oil palm expansion in Gabon

The SIAT group, a Belgian agro-industrial company, has operations in Nigeria, Ghana, Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire. The group’s main international bankers are: KBC Group (Belgium), BMI/SBI (Belgium), DEG (Germany), the African Development Bank and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) from the World Bank. As a result of a privatisation exercise implemented by the Government of Gabon in 2003, SIAT acquired the until-then state companies Agrogabon, Hévégab and the Ranch of Nyanga. In 2004 the take-over convention for these enterprises was signed and SIAT Gabon was created. The company owns oil palm and rubber plantations and allied processing industries such as palm oil mills, palm oil refining. Much of the areas chosen for the company’s expansion plans are almost entirely forested (6).

A pivotal struggle for forest and peasant communities is the one against land grabs and concentration of land ownership, which profoundly affects communities who depend on lands and forests for their survival and livelihoods. This struggle has become even harder, not only due to the expansion of agribusiness, mining, oil and gas, monoculture tree plantations, hydroelectric plants, climate-related projects, etc., but also because of the further interest of financial actors in acquiring land.

(1) This article is based on the study “Land grabbing and human rights: The involvement of European corporate and financial entities in land grabbing outside the European Union”, requested by the European Parliament subcommittee on Human Rights (http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/578007/EXPO_STU(2016)578007_EN.pdf), unless stated otherwise.

(2) http://www.columbia.edu/itc/sipa/martin/chad-cam/overview.html#project

(3) http://wrm.org.uy/articles-from-the-wrm-bulletin/section3/open-letter-on-eu-biofuels-policy/

(4) http://eia-global.org/blog/eia-leads-discussions-on-illegal-commodity-driven-forest-conversion-in-cong

(5) http://www.forest-trends.org/documents/files/doc_4718.pdf

(6) http://wrm.org.uy/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Etude_sur_limpact_Plantations_palmiers_a-_huile_et_hevea-_sur_les_populations_du_Gabon.pdf