Land conflict in Côte d'Ivoire: local communities defend their rights against SIAT and the state

It all started one morning in August 2011 when three village communities in eastern-central Côte d’Ivoire learned that a Belgian corporation called SIAT was about to move onto their land. Not long afterward, an agribusiness firm started putting in a rubber monoculture on 11,000 ha that the communities had neither sold nor ceded and that SIAT was not entitled to exploit.

Today, a visit to the affected villages – Famienkro, Koffessou-Groumania, and Timbo – is a saddening experience, and empty pantries are the communities’ daily lot. They now have to buy their food, but with what money? Many landless peasants have become dependent on SIAT to feed their families.

It is incumbent on the national authorities and their international partners to acknowledge and deal with the looming famine and food insecurity affecting this region. This report recounts the events occurred in the communities’ ongoing struggle to fend off the government of Côte d’Ivoire and the Belgian multinational SIAT. It seeks to revive the debate around the Ivorian government’s approval of a megaproject on land claimed by the communities of Famienkro. Are the legal loopholes exploited by the state an indication of its intent to rob communities of their land – all to please a rubber multinational?

Family farms sacrificed on the altar of agribusiness

In Côte d’Ivoire, the year 2014 was actively celebrated by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and many Ivorian NGOs as the International Year of Family Farming.1 A number of projects designed to protect small farmers were implemented, and the promotion of family farming was central to numerous debates and meetings. Then, in 2015, the country went on to pass an “Agricultural Orientation Act” an initiative aiming in part to support and promote to people’s food sovereignty.2

Despite these advances, the good intentions of the Ivorian political authorities remain beholden to the interests of agribusiness – the proof being that the SIAT project was allowed to trump family and peasant farming. The peasants of Famienkro found themselves faced with the dispossession of their land by SIAT’s machines and equipment, and the company seems determined to turn them into farm workers. In this way, rubber, with its disastrous impacts on biodiversity, is taking the place of crops that once provided food for people.

SIAT ignores free prior informed consent

It was in August 2011 that the communities of Famienkro, Koffessou-Groumania, and Timbo, located about 300 km from Abidjan, learned through the grapevine that a corporation was about to move on to their land.

A month later, on September 15, the representatives of the three villages were informed that the government had granted a concession covering a total of 11,000 ha to Compagnie hévéicole de Prikro (CHP), the Ivorian subsidiary of the Belgian corporation Société d’investissement pour l’agriculture tropicale (SIAT), for the purpose of establishing an industrial rubber plantation. Some of this land had been used between 1979 and 1982 by a government-owned corporation, SODESUCRE, for the development of sugarcane plantations. Since the end of the sugar project, the peasants had returned to farming on the site.

The communities were stunned. The sugar complex occupied only 5,500 ha, whereas the government had just granted 11,000 ha to CHP.

Furthermore, free prior informed consent (FPIC) by the local population is always required in such cases, especially when arable land is being granted to companies, regardless of whether they are domestic or foreign. This rule was instituted by the first president of the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire during the negotiations around SODESUCRE. Today, the villagers are wondering why the rule was ignored.

The King of the Andoh, His Majesty Nanan Akou Moro II, speaking through his representative Sinan Ouattara, confirmed that “we did not give our consent to this project, whose impact on our ancestral lands, territories, and natural resources is devastating. We refuse to let our land be stolen.” For 39 years the chief of this territory, the King of the Andoh reigns over the Coblossi tribe, who live in seven villages in the vicinity of Famienkro: Koffessou-Groumania, Sérébou, Kamélésso, Assouadiè, Morokro, Lendoukro, and Kouakoukro.

SIAT ignores Côte d’Ivoire’s legal framework

Article 39 of the Environmental Code of Côte d’Ivoire provides that the SIAT project, as a large project likely to have an impact on the environment and society, must undergo a prior environmental and social impact study.3 To date, SIAT has not completed such a study.

In 2015, when work on the rubber plantation had already begun, CHP made an application to the Agence nationale de l’environnement (ANDE), the public agency in charge of prescribing the environmental impact procedure. ANDE decided to order measures to correct the impact of the project. The terms of reference of the environmental and social impact study were drafted and sent to SIAT, which was to select a firm to carry out the study.

Under the regulations, the terms of reference are only valid for one year, but the impact study had yet to be submitted a year ago when we inquired into its status. As of this writing, according to information available from ANDE, the study has been completed and filed and is pending validation. In the absence of a prior environmental and social impact study, the company’s use of these lands and its implementation of the project violate the Environmental Code of Côte d’Ivoire.

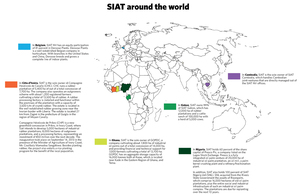

SIAT around the world

SIAT is a Belgian multinational claiming to “specialize” in tropical agriculture.4 In June 2013, it had some 175,000 ha under cultivation in Africa, Asia, and Europe.5 This powerful multinational, with capital of €31 million and a business volume of nearly €200 million, has holdings in palm oil, rubber, and grazing. SIAT’s head office is in Brussels and it is active in Belgium, Nigeria, Ghana, Gabon, Cambodia, and Côte d’Ivoire.

In Nigeria, SIAT holds a 60% stake in Presco Pic, a company listed on the Lagos Stock Exchange. Presco is a fully integrated palm oil production company. It owns 20,000 ha of oil palms, an oil mill, a fiber crushing station, and a refinery/fractionation plant.

In addition, SIAT is the sole owner of SIAT Nigeria Ltd (SNL). SNL acquired the Government of Rivers State’s holdings in Risopalm, including 16,000 ha of old oil palm plantations along with the entire corporate and industrial infrastructure associated with an industrial oil palm complex of this type. The plantations are to be renewed over the next decade.

In Ghana, SIAT is the sole owner of GOPDC, a company cultivating about 7,800 ha of industrial oil palms out of a total concession of 14,000 ha, and providing financial and technical support for 7,000 farmers cultivating a total of 13,700 ha. GOPDC has a refinery/fractionation station with a capacity of 100 tonnes per day along with a storage area that can accommodate up to 16,000 tonnes.

In Gabon, SIAT owns 99% of SIAT Gabon, which has 12,000 ha of rubber plantations and 5,000 head of beef cattle.

In Côte d’Ivoire, SIAT is the sole owner of Compagnie Hevéicole de Cavally (CHC), which has 5,400 ha under cultivation out of a total concession of 7,700 ha. The company also runs a sharecropping operation, with some 1,200 farmers producing 13,500 ha of rubber. There is a rubber processing plant on the plantation with a production capacity of 3,500 t/m of rubber crumbs. The property is located in the rubber-growing region near the border with Liberia.

CHP is a new concession on which SIAT plans to put in a 5,000-ha industrial rubber plantation, 8,000 ha of sharecropped fields, and a processing plant, for a total investment of €50 million over ten years. Apart from rubber, other crops to meet the needs of the population are also planned.

The concession was inaugurated in September 2013 in a ceremony attended by the Minister of Agriculture of Côte d’Ivoire, Mamadou Sangafowa Coulibaly.

In Belgium, SIAT NV holds an 81% stake in Deroose Plants, a Belgian horticultural concern. With branches in the United States and China, Deroose breeds and grows a complete line of indoor plants.

In Cambodia, SIAT is the sole owner of SIAT Cambodia, which handles Cambodian joint-ventures that are directly managed out of the SIAT NV offices.

The conflict worsens

SIAT’s ambition is to pursue its growth and increase its profits around the world, and in Africa more particularly, to the detriment of communities that have no assets other than land with which to feed themselves and earn a decent living. In the interests of achieving its goals, it has turned a deaf ear to citizens who challenge its projects in Africa under the slogan “No to Rubber!”

In the summer of 2015, an incident in which someone set fire to tractors and destroyed crops was laid to the door of the protesters. A few days later, the Gendarmerie Nationale responded with a heavy-handed operation that degenerated into a skirmish and left a mortal toll: two people shot to death in Famienkro and many more injured. The fatalities were Assué Amara of Koffessou, who died instantly from a bullet to the neck, and Ali Amadou of Timbo, who was hit in the abdomen and died the next day. There were also clashes pitting the protesters against supporters of the project.

Subsequently, numerous houses were burned down in Famienkro. Several opponents of the project fled to avoid reprisals. A total of 71 individuals, including the King of Famienkro, the chief of the village of Koffessou, and Sinan Ouattara, were arrested and held in M’Bahiakro prison after being detained for several days in Prikro, the seat of the commune. Daouda Mahaman, who was not present during the demonstration, was convicted on 28 July 2015 of arson targeting homes, causing a fire requiring eight engines to extinguish, destruction of “manmade” plants and trees, inflicting blows and injuries, insulting an officer in the performance of his duties, disturbing the peace, and illegal possession of firearms.

Siriki Koffi Abdoulaye (from Famienkro) died from lack of appropriate medical care on 3 January 2016 while detained in M’Bahiakro prison, bringing the death toll to three. Meanwhile, 38 people were released on 1 December 2015 after almost five months of pretrial detention.

Among them was N'Djoré Yao Kassoum, Chief of the village of Koffessou. Upon being released from detention under cruel and degrading conditions, he stated: “When the machines came to clear the land, all my bananas, taro, rice, manioc, corn, and cashews were destroyed. That’s why I called on the people to chase them off. I am blind, I have to eat. You destroyed my fields. What am I going to eat? I was unjustly imprisoned for defending my own land!”6 He died at 87 years of age, shortly after his release from prison on 26 May 2016.

SIAT covets sacred and heritage forests

Even as controversy continued to swirl around the Famienkro case, SIAT sought to control other lands in the western part of the country, where it already controls a vast area of rubber plantations through CHC.

SIAT CEO Pierre Vandebeeck emerged from a September 2017 meeting with the Vice President of the Republic to tell the press that he had had “very encouraging discussions concerning conservation of the Goin-Debé heritage forest.”7 SIAT evidently aims to control this 133,000-ha forest, the second-largest forest reserve in the country. Does it intend to raze the forest to make way for rubber or oil palm plantations? For the time being, all we know is that there are about 10,000 ha of virgin forest remaining in Goin-Débé.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) and many other organizations have attracted attention to the introduction of the concept of “agroforestry ” in the revised text of the Ivorian Forests Act, which is an attempt to reconcile monoculture with the existence of forests.8 This revision of the legal framework portends the transfer of responsibility for heritage forest management from the Ivorian government to private interests. According to HRW, “The decision to assign the management of the proposed category of Agro-Forests to private companies carries significant risks for the rights of occupants of protected forests, and for the forests themselves.”

Like the land issue, the issue of forests is a frequent source of intense conflict in Côte d’Ivoire. To neglect these realities and continue to allow companies to generate revenues, even if it threatens the survival of people and biodiversity, would be fraught with consequences. SIAT should endorse the recent appeal by numerous donors to the Ivorian authorities to radically rethink the country’s forest policy and strategy, as well as the impact thereof on the life of local populations.9

Government grabs land to benefit SIAT

The government claims ownership of the land on the pretense that it was made available to the Ministry of Agriculture in 1979 when the sugar complex was built. False, say the communities, who maintain that they never sold this land to the government; rather, they ceded it to SODESUCRE for the purposes of the complex, which was dismantled in 1982.

To date, the government has yet to produce any documents proving that the land was ceded to it by the local communities, nor has it proved that the customary rights of the aggrieved landowners were extinguished. This is the only administrative act that the government could adduce in support of its claims. The loss of customary rights to land normally entails payment of compensation, but no rights holder in Famienkro was ever compensated for loss of land rights in 1979. All that the government has done is to issue a series of decrees indemnifying peasants whose crops were destroyed to make way for the sugar complex.

A fraught legal battle

In 2013, in a final act of resistance, villagers opposed to the project took SIAT to the court of M’Bahiakro, the departmental seat, asking the judge to evict the company from the dispute land.

SIAT testified that the umbrella agreement it signed in 2013 with the Government of Côte d’Ivoire (represented by the minister of agriculture) gives it the right to develop the land. The company also adduced a land registration application for the 11,000 ha, filed by the minister of agriculture in the regional district of Baoulé on 24 April 2014. The Famienkro communities immediately opposed this registration.

In October 2014, the court ordered that a sequence of hearings be held to determine the nature of the contract covering the disputed land and whether or not the people’s customary rights had been extinguished. The following month, the ministry of agriculture, represented by Delbé Zirignon Constant, Director of Rural Lands, argued before the judge that “the question of whether or not the customary rights were extinguished has no bearing on the validity of the land transfer.” He contended as well that when SODESUCRE was established, the government compensated the peasants for their destroyed crops. He added that “since the government owns the disputed area, the question of the extinction of customary rights is immaterial.” Finally, he stated that vacant and unoccupied lands belong to the state.

But the disputed lands are not vacant or unoccupied – on the contrary, the communities have been living there and cultivating them for a very long time. Furthermore, a distinction must be made between customary rights and compensation for crop losses; in particular, the payment of such compensation does not in and of itself extinguish these rights.

By appropriating the land belonging to the people of Famienkro, the government is also violating the Rural Land Act of 1998, which gives communities a period of 10 years, or until 2023, to assert their customary land rights.10

In addition, the Ivorian government seems to have no interest in implementing or enforcing the FAO voluntary guidelines on the responsible governance of land tenure, even though it committed to doing so in 2014.11,12

A second hearing takes place behind closed doors

When the land restoration ordered by the court of M’Bahiakro came to an end, the judge found that there was no evidence of extinction of rights or of any contract in which the communities had given up their rights to these lands. He decided to hold a second hearing.

The communities were not invited to this second hearing. It was only much later that they learned that the court had thrown out their case on 24 November 2016. Ruling on the community’s demand to evict the company, the judge held that the communities had not denied that they had “ceded the disputed area for the establishment of a sugar complex.”

He added that the Famienkro communities had not produced “a lease signed with the government, with a term coinciding with the cessation of operations at the sugar complex, which would justify the immediate return of this land area to them.”

Our analysis is that the communities hold customary rights in these lands. It is not up to them to prove ownership: it is up to the government to prove that the land was ceded to it and that it is the undisputed new owner.

In 2015, despite the nonexistence of a deed granting the government ownership of the land formerly used by SODESUCRE, it managed to register in its name about 11,000 ha of land in Famienkro.

SIAT, like other multinationals in Côte d’Ivoire, is operating on contested land. The agribusiness steamroller impelled by international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and AGRA continues its advance across Côte d’Ivoire and throughout Africa. Communities are forced to hand their land over to multinationals claiming to want to “feed Africa,” to fight hunger.13 But hunger was never a problem for the courageous peasants of the seven villages affected by the rubber plantation. It is now.

Appendix: Public-private partnerships in agriculture, a lopsided partnership

In the context of its partnership with the state, SIAT asserts that it will directly create 8,000 jobs. The goal is perhaps noble, but SIAT does not mention the thousands of other jobs that will be destroyed in these villages. How many of their estimated 40,000 inhabitants will find jobs with SIAT?

Agribusiness multinationals love to toss around job creation figures, but they never want to admit that their investments often destroy a whole way of life – that they eliminate the occupation of small farmer.

SIAT’s project falls within the framework of the country’s National Agricultural Investment Program for 2012–2015, which reserves a privileged place for public-private partnerships (PPP).

In an April 2016 interview with the Ivorian press at the 29th FAO Regional Conference, Ibrahim Coulibaly, Vice-President of the West African Network of Peasant and Farmer Organizations (ROPPA), referring to PPPs, said that some consistency has to be brought to agricultural policymaking. Many actors have noted that PPPs only benefit foreign corporations, which are given numerous enticements, including subsidies, and that domestic firms cannot compete with them. “They take us for fools,” said Mr. Coulibaly.

As noted by Oxfam, these PPPs reinforce inequality and threaten the land rights of African populations.14,15

In Famienkro, aside from the company’s small permanent staff, somewhere between 800 and 1,000 day labourers were reported to have jobs on SIAT’s plantations, a figure that has apparently declined at time of writing.

According to one worker: “Per month, working six-day weeks, we can earn 39,000 CFA francs (about €60). As for me, I’m in irrigation so I work every day, and I can also get overtime. That’s how I manage to earn 50 or 60 thousand CFA francs (€77–92). If you don’t do overtime, your monthly salary works out to 39,000.”

Who really benefits from these partnerships? Judging by the wages, not the population.

Anyone with a genuine concern for alleviating poverty and hunger – a concern professed by initiatives such as the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition and GROW Africa – has to ask serious questions about these partnerships.

References

1 B. Kouamé, “Agriculture familiale: La société civile prépare la célébration de l’année internationale,” Akody, 6 July 2013, online at https://www.akody.com/cote-divoire/news/agriculture-familiale-la-societe-civile-prepare-la-celebration-de-l-annee-internationale-3202

2 Loi no. 20/5-537 du 20 juillet 2015 d'orientation agricole de Côte d’Ivoire, published in the Journal officiel de Côte d’Ivoire on 19 August 2015, online at http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/ivc155706.pdf

3 Loi n° 96-766 du 3 octobre 1996 portant Code de l’Environnement, online at http://www.droit-afrique.com/upload/doc/cote-divoire/RCI-Code-1996-environnement.pdf

4 SIAT website, http://www.siat-group.com/

5 CNCD, 11.11.11, AEFJN, Entraide et Fraternité, FIAN Belgium, Oxfam-Solidarité, SOS Faim, “Ruées vers les terres? Quelles complicités belges dans le nouveau Far West mondial ?,” June 2013, Brussels, online at https://www.cncd.be/IMG/pdf/Etude_Accaparements.pdf

6 Field research, 2016.

7 Présidence de Côte d’Ivoire, “Le Vice-Président de la République a reçu en audience le PDG du groupe belge SIAT,” online at

8 Human Rights Watch, “Letter on Rights Impacts of Draft Policy for Forest Preservation and Rehabilitation,” 26 October 2017, online at https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/10/26/cote-divoire-letter-rights-impacts-draft-policy-forest-preservation-and

9 Anderson Diédri, “Gouvernance forestière: des diplomates mettent en garde Amadou Gon,” Eburnie Today, 25 April 2017, http://eburnietoday.com/gouvernance-forestiere-diplomates-mettent-garde-amadou-gon/

10 Loi n° 2013-655 du 13 septembre 2013 relative au délai accordé pour la constatation des droits coutumiers sur les terres du domaine coutumier et portant modification de l'article 6 de la loi n° 98-750 du 23 décembre 1998 relative au Domaine Foncier Rural, online at http://www.foncierural.ci/index.php/reglementation-fonciere-rurale/21-la-loi/58-la-loi-n-2013-655-du-13-septembre-2013-relative-au-delai-accorde-pour-la-constatation-des-droits-coutumiers-sur-les-les-terres-du-domaines-coutumier-et-portant-modification-de-l-article-6-de-la-loi-n-98-750-du-23-decembre-1998-relative-au-domaine-fonci

11 Article 5.3 of the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security reads as follows: “States should ensure that policy, legal and organizational frameworks for tenure governance recognize and respect, in accordance with national laws, legitimate tenure rights including legitimate customary tenure rights that are not currently protected by law; and facilitate, promote and protect the exercise of tenure rights.” FAO, 2012, online at http://www.fao.org/docrep/016/i2801e/i2801e.pdf.

12 GRAIN and AFSA, “Land and Seed Laws under Attack: Who Is Pushing Changes in Africa?,” 21 January 2015, online at https://www.grain.org/article/entries/5121-land-and-seed-laws-under-attack-who-is-pushing-changes-in-africa.

13 Ossène Ouattara, “Les solutions de la BAD pour ‘nourrir l’Afrique,’” Info du Zanzan, 26 June 2016, online at http://infoduzanzan.com/les-solutions-de-la-bad-pour-nourrir-lafrique/

14 Robin Willoughby, “Moral Hazard? ‘Mega’ Public-Private Partnerships in African Agriculture,” OXFAM, 1 September 2014, online at https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/oxfam_moral_hazard_ppp-agriculture-africa-010914-embargo-en.pdf.

15 “Agriculture: les partenariats public-privé géants menacent les droits fonciers des populations africaines,” Jeune Afrique, 5 September 2014, online at http://www.jeuneafrique.com/6957/economie/agriculture-les-partenariats-public-priv-g-ants-menacent-les-droits-fonciers-des-populations-africaines/.