Access to Nicaragua’s eastern indigenous autonomous zones is limited, with many areas only accessible by boat or on foot. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe for Mongabay)

Nicaraguan beef, grazed on deforested and stolen land, feeds global demand

BY MARIO RAUTNER, SANDRA CUFFE

Eduardo Solano did not say much on the way home. He bought some oranges from a fruit vendor at a makeshift dock in Bluefields, the capital of Nicaragua’s South Caribbean Autonomous Region, and settled in for the three-hour boat journey that would get him most of the way home to Tiktik Kaanu, an indigenous Rama community he leads.

The other passengers were heading past Tiktik Kaanu to an illegal settlement where non-indigenous Nicaraguans have invaded indigenous communal lands, cleared the forest, and brought in cattle to graze. Traveling through the indigenous territory, the boat glided past towering mangroves and stretches of forest lining the Kukra River, where turtles, herons and blue morpho butterflies provided flashes of color against the walls of green. Here and there the forest gave way to clearings and pasture along the riverbank.

“Our lands are reduced,” Solano said after disembarking and hiking the rest of the way home. “They come with the idea of destroying the forest. It is not like us Rama, we protect it. But they come in cutting down trees, sowing pasture, and then bringing in cattle.”

Tiktik Kaanu is one of the nine communities — six indigenous Rama and three Afro-descendant Kriol — that govern Rama-Kriol communal lands. After years of struggle and international pressure, the Nicaraguan government granted a collective land title just over a decade ago covering more than 4,400 square kilometers (1,700 square miles) of land and nearly as much sea. But subsequent steps to ensure property rights within the title faltered, and invasions of communal lands by outsiders and cattle are on the rise.

“After we received our [land] title, many people came in,” Solano told Mongabay during a visit to the region in October. “We’re invaded all over.”

The lay of the land

Most indigenous people in Nicaragua live in two densely forested regions along the fertile Caribbean coast — the South Caribbean Autonomous Region (RAAS) and North Caribbean Autonomous Region (RAAN) — that were established in 1987 during the “Contra War” waged by U.S.-backed forces against the post-revolutionary government led by Daniel Ortega. The autonomous regions were afforded a measure of self-rule. But after the election of Violeta Chamorro in 1990 concessions were granted to logging and mining companies and demobilized combatants were encouraged to resettle there, sparking tensions that persist to this day.

Tiktik Kaanu, or Leaf-Cutter Ant Hill in the Rama language, is a village of about 130 people living on either side of a bend in the river. Residents subsist on small-scale agriculture, producing enough to feed themselves and a modest surplus to sell in Bluefields, the regional capital. The community is only accessible by boat or on foot, but its relative proximity to Bluefields and to a highway connecting Bluefields to Nueva Guinea, the livestock hub of the region, makes Tiktik Kaanu more accessible than many other parts of Rama-Kriol territory.

A law laying out a five-step process to securing collective land titles in the RAAS and RAAN was introduced in 2003, Law 445, after indigenous Mayangna communities two years earlier took a South Korean logging company to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and won. The law obliged the government to remove non-indigenous settlers and concessions from communal land. Despite a slew of land titles being issued following the re-election of President Ortega in 2006, indigenous groups say his administration has yet to implement this crucial phase of the plan, known as saneamiento, or “cleaning up.”

Despite the new rules, thousands of settlers continued to arrive in the autonomous zones, many claiming to have purchased land titles. As a result, violent land conflicts have persisted, displacing thousands of indigenous people and leading to dozens of killings.

In the past five years, 40 indigenous people have been killed, more than 40 injured, and more than 40 kidnapped in cases related to land invasions, according to the Center for Justice and Human Rights of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua, an NGO that provides support and legal assistance to indigenous peoples and Afro-descendant communities.

Most of the attacks have taken place in the northern region, home to indigenous Miskito and Mayangna peoples, whose struggle led to the landmark ruling in 2001. But following the decision, the government has dragged out the court-ordered demarcation process for years.

More recently, Mayangna communities in and around the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve have been subject to violent attacks and incursions by armed civilians seeking to exploit their forest and lands, sparking panic and mass displacement. On Jan. 29, dozens of armed men invaded the Mayangna community of Alal, located inside the Bosawás reserve, burning homes and killing at least four indigenous residents. A report published last month by the Oakland Institute accused President Ortega of downplaying the crisis and failing to protect indigenous communities.

‘They come with dogs and weapons’

Tiktik Kaanu, or Leaf-Cutter Ant Hill in the Rama language, is a village of about 130 people living on either side of a bend in the river. Residents subsist on small-scale agriculture, producing enough to feed themselves and a modest surplus to sell in Bluefields, the regional capital. The community is only accessible by boat or on foot, but its relative proximity to Bluefields and to a highway connecting Bluefields to Nueva Guinea, the livestock hub of the region, makes Tiktik Kaanu more accessible than many other parts of Rama-Kriol territory.

Within titled Rama-Kriol lands, Mongabay saw evidence of incursions by outsiders: established clearings, newly razed areas, and cattle, both with and without ear tags — a telltale sign that livestock had been moved into the area in a process known as cattle laundering.

The calls of howler monkeys are audible from the porch of Solano’s wooden stilt home. There are also spider monkeys, white-faced capuchins, coatis, and other mammals in the area. But the wildlife pales in comparison to what Solano says he saw as a child growing up on the reserve, when it was not unusual to see tapirs bathing in the river.

“When there were not many people around, we had all kinds of animals because there was a lot of forest, but when outsiders, the non-indigenous, come in, the animals flee,” he said. “They come in with dogs and weapons. They raze everything and it’s worrisome for us as indigenous peoples because it is our livelihood.”

Solano is Tiktik Kaanu’s representative in the Rama-Kriol Territorial Government (GTRK), which comprises leaders from each of the nine communities, who are elected by local assemblies. The GTRK is tasked with managing this vast territory with little to no support from the central government, despite the government’s legal obligation to protect the communities’ land rights. Tiktik Kaanu is far from alone in facing the threat posed by settler communities.

Forging land documents

Non-indigenous Nicaraguans arrive from Chontales, Juigalpa and other areas west of the Caribbean autonomous regions, Dalila Padilla, the GTRK secretary, told Mongabay at her office in Bluefields in October. Some are big-time cattle ranchers. Others are poor families trying to eke out a living. Either way, they cannot legally own property in Rama-Kriol territory.

Some non-indigenous Nicaraguans do not know they are invading communal indigenous lands. Their lawyers are usually aware of the situation, but it does not stop some of them from drawing up land sale documents, according to Padilla. “The expansion of cattle ranching in the territory is one of the major challenges we face,” she said. “When [outsiders] invade, they invade lands and then convert it to pasture. They turn it into a ranch for cattle. All over the territory, they only focus on cattle ranching.

“Many lawyers do things for money,” she added. “If a lawyer gives them a document, they think it is legal but the truth is, it is not.”

Indigenous communities and the GTRK have developed policies to address the problem. Under the agreements, communities may vote to permit outsiders to remain, but settlers cannot sell or expand land holdings, bring more settlers in, or exploit communal resources, and they must respect the authority of indigenous leaders and decisions made in community assemblies.

However, without the political will and resources from the Nicaraguan authorities to follow through with their obligation to enforce land rights within the title, the process relies on voluntary engagement by settlers. It also does not apply in the Indio Maíz Biosphere Reserve, much of which is within the Rama-Kriol title. As the last significant remaining tract of protected forest in the southern region, its increasing destruction from incursions, cattle ranch expansion and forest fires has caused widespread alarm in Nicaragua. “Indio Maíz is in danger, and not just the forest but people too, because there are threats against the Rama,” Padilla said.

Three of the nine communities in Rama-Kriol lands are located inside the Indio Maíz reserve. Corn River, a Kriol community, and Greytown, a mixed community, are both located on the coast. But Indian River, a small Rama community, is right in the heart of Indio Maíz, and its residents and leaders have faced threats from outsiders invading the biosphere to clear land for cattle.

“The indigenous leaders of Indian River have shown up where non-indigenous people are to tell them the lands are communal, that the lands belong to them, and that people need to go back to where they came from,” Padilla said. “The non-indigenous began threatening the Rama, trying to displace them so they can have all the land.”

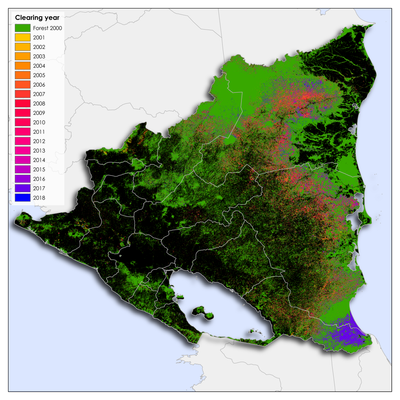

Nicaragua’s arc of deforestation

No other Central American country has lost forest as quickly as Nicaragua since 2000. According to Global Forest Watch, the total forest cover in Nicaragua decreased by 18% between 2001 and 2018, and all of that forest loss occurred in natural vegetation. Within the indigenous autonomous zones, the deforestation rate was even higher. The northern zone lost 20% of its forest cover and the southern zone lost 27% during that period.

An analysis of deforestation data provided to Mongabay by the Gibbs Land Use and Environment Lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison shows how the land clearing has spread eastward into the indigenous territories in line with reports of rising encroachment by settlers.

In the RAAN, large-scale deforestation began in 2007 along the road from Matagalpa and increased significantly after 2010, with the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve in the region’s northwest particularly badly hit. Bosawás is estimated to have lost about 100,000 hectares (250,000 acres) of forest cover since 2011.

In the RAAN, large-scale deforestation began in 2007 along the road from Matagalpa and increased significantly after 2010, with the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve in the region’s northwest particularly badly hit. Bosawás is estimated to have lost about 100,000 hectares (250,000 acres) of forest cover since 2011.

In the RAAS, deforestation appears to have accelerated rapidly after 2010 in an advance eastward toward the Mosquito Coast, particularly in the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve to the south of Bluefields — where large-scale logging in 2017 and 2018, also driven by settler invasions for cattle ranching, has decimated forest stocks — and in the Cerro Wawashang Natural Reserve to its north.

While Nicaragua is a relatively minor producer of beef compared with major exporters such as Brazil, its sales have steadily risen in recent years. Beef exports rose from 60% of total production in 2006 to more than 95% in 2019, a higher proportion than any other country, according to the U.S. Foreign Agricultural Service. The United States is Nicaragua’s main export destination for frozen beef, accounting for almost two-thirds of the total. An expected lifting of an import quota assigned under the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement may see the figure rise yet further.

Most of the beef imported from Nicaragua is not directly purchased by consumer-facing companies. Instead it is procured by mid-sized trading firms such as Gurrentz International, Northwestern Meat, ASC–Meyners, and Export Packers. Nicaraguan beef is thought to be used largely for highly processed products such as beefburgers and pet food.

The intermediary companies listed in U.S. customs data as having received beef from Nicaragua in 2019 did not respond to questions about their supply chain, but export data show that all four of the companies bought beef from Industrial Comercial San Martín, the second-largest exporter of beef in Nicaragua. Two other Nicaraguan slaughterhouses, Nuevo Carnic and Matadero Central, also did not respond to Mongabay’s requests for comment.

While few of the slaughterhouses supplying U.S. firms were willing to speak on record, an employee of Industrial Comercial San Martín told Mongabay that as much as 70% of its beef comes from the RAAN alone. The most important supplier is the municipality of Siuna, which is also in the top three municipalities in terms of deforestation. According to Salvador Flores, Industrial Comercial San Martín’s exports manager, the origin of the beef within Nicaragua is noted on box labels.

The lack of full traceability makes it impossible to differentiate between beef linked to deforestation and human rights abuses, and that produced legally and more sustainably. That leads to problems for major buyers.

Both Nestlé and Cargill, two of the companies processing beef from Nicaragua, confirmed in statements to Mongabay that they can only trace the beef to the slaughterhouse, not to its origin. A McDonald’s spokesperson said the company does not currently source beef from Nicaragua. A spokesman for JBS, the largest meatpacking company in the world, did not respond to requests for comment by the time of publication.

Nestlé said that while only a small amount of its total U.S. beef supply comes from Nicaragua, it was “engaged with our supplier to ensure they can demonstrate that the beef can be traced even further, to the farm of origin, and that it is not linked to deforestation or land and human rights violations.” Nestlé is not the only company sourcing and selling beef from Nicaragua that may have originated in biosphere reserves or titled indigenous lands. However, other companies are less transparent when it comes to the origin of their beef and do not publish supplier lists.

In response to questions about its supply chain, Cargill said that it sources “small amounts” of beef from Nicaragua and that while it also has a policy to eliminate deforestation from its supply chain, it can only track Nicaraguan beef back to the production facility.

The bovine laundromat

There are 135,000 registered ranchers in Nicaragua, according to Ronald Blandón, general manager of the National Commission of Cattle Producers of Nicaragua. About 85% of their properties are registered in the country’s bovine traceability program, and that is where Nicaragua has made the most progress. “A bovine traceability program is a process that does not happen from one year to the next. It is difficult,” Blandón said.

Nicaragua’s traceability program is managed by the Institute of Agricultural Protection and Health, a government body under the agriculture ministry. Producers and their properties are given unique codes, identification numbers linked to registered properties are issued for cattle ear tags, and transport route documentation is provided by municipal authorities.

“The principal aim of traceability is to determine the origin of the product, in other words, this animal was produced in Matagalpa or was produced in Managua, or was produced in which property, so that in the event that the consumer has some health problem, it is possible to find the place where the product originated,” Blandón said.

Authorities would not register a property inside a protected area or issue ear tags to cattle in a property inside a protected area because it would be illegal, he added. If there are cattle registered with the traceability program grazing inside a protected area, such as the Indio Maíz Biosphere Reserve in the southern region, the only feasible explanation, according to Blandón, would be a failure in transport control, with unrecorded movements.

“At slaughterhouses and auctions, where there is the most movement of cattle every day, they cannot receive a truck with cattle for slaughter if it is not accompanied by the transfer guide, which is granted by the municipal government and reviewed by local police. Without that, they cannot accept cattle,” Blandón said.

“Let’s say if you saw animals with the traceability ear tags in areas where cattle ranching should not occur, it’s that some producers took cattle from their properties that were registered in places where cattle ranching is permitted and sent them to that area. That is the only explanation I have. And it could be that they take them there, fatten them, take them out, and market them,” he added.

Amaru Ruíz is the director of Fundación del Río, a Nicaraguan environmental NGO that has monitored the cattle trade inside Indio Maíz for several years. The work Ruíz and his colleagues were doing drew the attention of the ranchers, prompting threats that led him to flee to Costa Rica. Speaking by phone from his new home, he said the evidence his team had gathered showed that cattle were laundered from the Indio Maíz Biosphere Reserve before being sent to market.

The group released its findings on June 5. The foundation has identified the locations of scales used to weigh the animals and a number of intermediaries who broker the sale of cattle coming from the reserve. His files show there are scales both inside and along the edge of the biosphere reserve. Through a network of dozens of intermediaries, cattle grazed inside Indio Maíz make their way to the slaughterhouses of some of the country’s main beef processing companies, the research suggests.

“I think it is important to say that the traceability mechanism in Nicaragua does not work,” Ruíz said. “You cannot be sure that cattle really comes from a certain property. You cannot ensure that, even if it is registered. So at least from the experience in Indio Maíz and in the southeast, we know that the traceability process is not working because there is no rigorous process of inspection of what is happening. If there were, there would be no cattle inside Indio Maíz, and there is cattle inside Indio Maíz.”

Cattle rancher associations have acknowledged the issue and pledged to stop their members operating in protected areas. But not everyone is a member of the associations, and the latter have no control over non-members.

“The agricultural frontier has advanced exponentially, and that is primarily due to large-scale cattle ranching,” Ruíz told Mongabay. “The state promoted it as public policy. Obviously that is going to have repercussions, and one of the repercussions it has had is deforestation in the [Indio Maíz] reserve. In Bosawás, it is the same. The same phenomenon that is occurring in the southeast is occurring in Bosawás.”