Bloomberg | 15 November 2018

Harvard spent $100 million on vineyards. Now it's fighting with the neighbors

Harvard spent $100 million on vineyards. Now it's fighting with the neighbors

By Michael McDonald

Four years ago, Harvard University bought an old cattle ranch in the foothills of the Sierra Madre Mountains. On an arid expanse north of Santa Barbara, California, the school’s endowment set out to make money from a notoriously tricky business: vineyards.

Thirsty wine grapes need water, a lot of it. So Grapevine Capital Partners, which manages Harvard’s investment, planned to dig huge ponds to store groundwater as part of an irrigation system for thousands of vines.

For the moment, though, Harvard’s endowment has reaped mostly bitter fruit from this purchase, one of its more than a dozen investments in California vineyards over the last six years. Skeptical locals say the school’s plan threatens the region’s scarce groundwater. With supplies considered critically depleted, county officials agreed, delaying the project for an environmental review. Harvard, which declined to comment, has appealed, and a hearing is scheduled for early next year.

“We’re very supportive of agriculture, but we don’t want agriculture to dry up our resources,” said Robbie Jaffe, who runs a neighboring vineyard with her husband and is leading the opposition. “This has the potential to be further devastating to our very limited basin.”

The fight illustrates the risks that Harvard’s endowment, the largest in higher education, once embraced with its unusual strategy of investing directly in massive agriculture projects around the world. At its peak, Harvard’s farmland spanned 2 million acres. Through companies it controlled, Harvard bought Central American teak forests, a cotton farm in Australia, a eucalyptus plantation in Uruguay, and timberland in Romania.

For more than a decade, such investments paid off. But the global commodities boom went bust after the 2008 financial crisis. This exotic fare contributed to the endowment’s lackluster results, among the worst of any major endowment: a 4.5 percent annual return for the decade ended in June. Harvard gained 10 percent in the year through June, one of the lowest returns in the Ivy League.

“Agriculture entails a lot of risks that you don’t get in other industries,” said Madeleine Fairbairn, an assistant professor of environmental studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “Many institutional investors underestimated the complexities.”

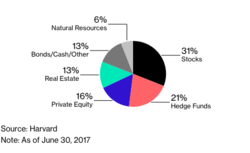

To turn around the fund, Harvard Management Co., the unit overseeing the endowment, hired N.P. “Narv” Narvekar from Columbia University in 2016. He has since retreated from natural resources and other direct investments. Last year, Narvekar wrote down the value of timberland and farms in the portfolio by $1 billion. They now make up less than 6 percent of Harvard’s $39 billion endowment, down from 13 percent five years ago.

Exotic Bets

The farmland investments led to headaches alien to those who stick to plain-vanilla stocks and bonds. In Brazil, for example, a public prosecutor’s office has said that it may sue to reclaim part of a farm the size of Phoenix, Arizona, after finding that titles for about two-thirds of the property are invalid.

The farmland investments led to headaches alien to those who stick to plain-vanilla stocks and bonds. In Brazil, for example, a public prosecutor’s office has said that it may sue to reclaim part of a farm the size of Phoenix, Arizona, after finding that titles for about two-thirds of the property are invalid.

In Australia, a company working for Harvard harmed an Aboriginal burial site when it was digging irrigation canals for one of the endowment’s cotton farms, according to a government inquiry. In South Africa, another project sparked conflict with black families denied land rights for cattle grazing and access to burial sites.

Harvard’s California conflict followed a vineyard-buying spree that began in 2012. Don’t look for Harvard-branded bottles of Crimson Grand Cru, though. The school is merely selling grapes that will blend anonymously into other wines.

The endowment spent about $100 million on more than a dozen properties. The school bought most of the land near the state’s Central Coast, famed for its wineries. Its value has since increased, according to the endowment’s tax filings.

One investment stood apart because it is further inland. In 2014, a company controlled by the endowment paid about $11 million for 8,700 acres of grazing land from the North Fork Cattle Co. in the Cuyama Valley.

Sour Grapes

Near a national forest, it is a wild and dusty place, as far from Harvard’s urbane campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts as is possible in America. Bobcats and coyotes prowl a habitat, where little more than the toughest scrub and bushes thrive. Once oil country, the lonely masts of the occasional derrick still dot the horizon. In this forbidding landscape, Harvard is cultivating a tenth of its land for a vineyard roughly the size of New York’s Central Park.

In the region, fights over water are common; one involving Harvard has spilled into public view. In 2014, amid an epic drought, California legislators passed a law restricting groundwater extraction. Parched Cuyama Valley needed to develop a sustainability plan by 2020.

Enter Jaffe and her husband Stephen Gliessman, a University of California ecology professor who specializes in environmentally sustainable agriculture. Near Harvard’s property, they raise grapes and olives at their five-acre Condor’s Hope Vineyard. The couple use a process called “dry” farming; it seeks to capitalize on existing rainfall, rather than massive irrigation projects. They say their well levels have dropped since Harvard began farming.

Jaffe and Gliessman assembled a team to fight a county decision: approving three huge Harvard “frost ponds,” as part of an existing irrigation system. In winter, workers would use water from the ponds to spray plants, protecting them from frost. The couple said that would tax groundwater supplies too heavily. “We’re worried,” Gliessman testified in September before Santa Barbara County’s planning commission. The board voted 3-2 to order an environmental review.

Harvard appealed the county’s decision. It also wants an exception from the new groundwater regulations. In April, Ray Shady, a company representative, offered a rationale. He argued that a fault line separates the western valley, where the Harvard vineyard is situated, from the rest of the region. As a result, he said, the vineyard shouldn’t be subject to the same strict rules as other growers.

For now, neighbors say the region lacks the water necessary for Harvard’s grand irrigation plans. “I’d love to see the whole valley green,” said Randall Tognazzini, who owns a ranch in Cottonwood Canyon, near Harvard’s vineyards. “But it’s just not happening.”