Global Trade Review | 09-11-21

‘Land grabs’ linked to major commodity supply chains will increase

by

Expropriation of land to make way for commodities is posing risks to corporates and investors as well as the environment, with illegal grabs set to increase as demand for food and materials rise.

Thousands of people are illegally forced from their homes every year for miners and farmers to produce commodities, such as palm oil and cobalt, that find their way into major supply chains.

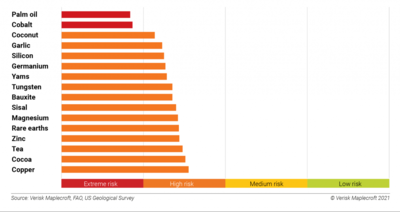

According to research by risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft, which analysed 170 commodities, palm oil and cobalt are at “extreme” risk of land grabs (figure 1). Other commodities such as silicon and copper that are central to a low-carbon transition, for example in battery production for electric cars, as well as garlic and coconut are also often linked to expropriation.

“As demand grows, we are expecting more incidents of this type in the commodities we have flagged – especially if issues around corruption and around indigenous peoples’ rights aren’t addressed,” Will Nichols, head of environment and climate change research at Verisk Maplecroft, tells GTR.

Palm oil is most exposed to land grabs because Indonesia, the biggest producer of the commodity, is known for weak practice in this area. “The country produces more than half the world’s palm oil and land conflicts are on the rise,” reads the report.

Meanwhile cobalt, the other material rated as extreme risk, has long been linked to child labour in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which accounts for around 70% of the world’s supply of the metal. In 2019, a lawsuit was filed against tech companies including Google and Tesla over the deaths of Congolese children in cobalt mines. The case was recently dismissed over a lack of evidence connecting the companies to the mines.

While there is no established link between the firms and the mines, in general it is “very difficult” for companies to have visibility beyond tier one suppliers, says Nichols. Cobalt is used in the manufacture of batteries for electric vehicles, which are important in the low-carbon transition. However, mining cobalt or other commodities that will power economies of the future should not leave behind a trail of social disasters, say campaigners. “The energy solutions of the future must not be built on human rights abuses,” warned Seema Joshi, then head of business and human rights at Amnesty International, in late 2017.

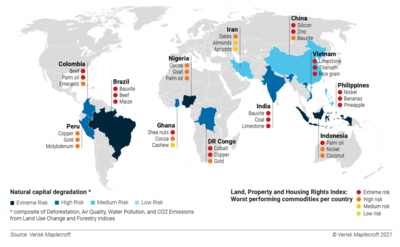

Power and coal at Cop

According to the report, there is a “clear link” between land grabs and the environment (figure 2), with expropriation fuelled by weak governance and corruption. As such, it is important to connect the ‘E’ (environmental) in ESG with the ‘S’ (social) and ‘G’ (governance), says Nichols. He believes that the two latter letters are at times “sidelined” in favour of the environment, with much of the focus of the Cop26 climate summit on “power and coal” and safeguarding nature.

“It’s easy to see, particularly in countries where governance is weak or where they are highly reliant on commodity exports, how land grabs and subsequently natural capital degradation is going to be on the rise,” he adds.

At the Cop26 summit in Glasgow, which is drawing to a close this week, leaders have promised to end and reverse deforestation by 2030. Some have questioned Indonesia’s commitment to that pledge after the country’s environment minister, Siti Nurbaya Bakar, called the deal “unfair”. Governments signed a different global pact to end deforestation by 2030 in New York in 2014, with little progress having been made since. The latest pledge, however, includes US$19.2bn of public and private funds, which many believe could make the difference between success and failure.

The private sector has an important role in protecting against land grabs. “It seems like almost every month there’s some court case or scandal about banks financing particular areas, or corporates trashing indigenous areas. Part of that is just poor [corporate] policy,” says Nichols.

In a report last month, campaigners accused banks of helping fuel deforestation and environmental crimes by financing major commodities producers and trading houses. The research by NGO Global Witness examined financing arrangements for 20 companies in beef, soya, palm oil, pulp and paper, rubber and timber supply chains it identified as “the most harmful and well-established firms”.

Last year, the campaign group urged international banks to stop funding three meat trading companies – JBS, Marfrig and Minerva – in Brazil, accusing the trio of contributing to deforestation in the Amazon.

Meanwhile, Nichols says investors are “using how well corporates address these issues as a window into their overall organisation and overall prospect as an investment”. “So, if you’re not taking these risks seriously, investors are going to know that, and it could well lead to issues in terms of accessing finance and around credit.”

While he remains unsure of whether two weeks of Cop can drive effective action on ESG issues, he does believe “the social risks side of things are certainly picking up in terms of investor interest”. That, he adds, should filter down to corporate interest.