Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

September 25, 2009 Papua New Guinea, the independent eastern half of the world's second largest island (New Guinea), houses one of the planet's last frontier forests. These forests support a wealth of plants and animals as well as the Earth's most diverse assemblage of cultures—some 830 languages are spoken in Papua New Guinea (PNG), representing more than 12 percent of the world's 6,900. But PNG's forests are fast-changing. Between 1972 and 2002 PNG lost more than 5 million hectares of forest, trailing only Brazil and Indonesia among tropical countries. Forest loss has been primarily a consequence of industrial logging and subsistence agriculture, but large-scale agroindustry—especially development of oil palm plantations—has emerged as an important new driver of land use change. Dozens of international companies have set up operations in the country over the past decade, including Cargill, an agribusiness giant based in Minneapolis.  Matilda Pilacapio.

Matilda Pilacapio. |

While Cargill says it is committed to sustainable and responsible palm oil production across its three plantations in PNG, the firm has been targeted by local and international NGOs, which claim it has polluted rivers and deceived local communities into signing agreements they do not understand. Some landowners say they are receiving few of the benefits oil palm promised to deliver, while losing their independence—they are now reliant on an export-oriented crop they can't eat. Opposition to further oil palm expansion is now growing, especially in Oro Provice, where Cargill's plantations are based.

A chief complaint is the tactics palm oil companies use for acquiring land for oil palm development. The Rainforest Action Network (RAN), a San Francisco-based activist group campaigning against palm oil, says that plantation firms often deceive locals into signing what are essentially debt-bondage contacts.

- In Papua New Guinea, the right of communities to own land is enshrined in the constitution. In fact, 97 percent of land is community-owned. Therefore, in order to expand palm oil plantations, companies must find ways to claim the land for themselves. They rely heavily on long-term leases that strip people of control of their land. Companies do this through two distinct methods: 1) mini-estates, and 2) small-holder schemes. With mini-estates, community members enter into joint-venture partnerships with Cargill in which the company charges the community for all inputs, labor and transport, and then take 90 percent of the profit. The people must continue to plant oil palm until their debts are paid off.

In small-holder projects, land owners commit small amounts of their land to palm oil plantations. With this scheme, small holders become increasingly dependent on the companies for fertilizers and seeds, and they end up increasing the amount of acreage devoted to the companies’ cash crop. In practice, this means that although the farmers are the formal land owners, they have no real control of their land.

Matilda Pilacapio, a former provincial government official and human rights advocate from Milne Bay, PNG, is among those landowners who oppose Cargill. Pilacapio is working with a local group, Milne Bay Women in Agriculture, to strengthen traditional agricultural systems in response to Cargill's expanding oil palm operations in the region. She is also taking her complaints directly to Cargill's hometown. Next week, with the help of RAN, Pilacapio will speak in Minneapolis about the situation in PNG.

In an exchange with mongabay.com, Pilacapio outlined some of her concerns with oil palm development, including her belief that local people often don't understand the terms offered to them by developers. Pilacapio hopes to see local communities embrace agroforestry and intercropping as a more sustainable alternative to industrial plantations.

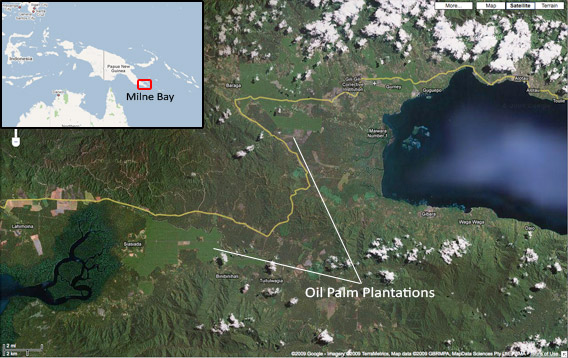

Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea

Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea |

AN INTERVIEW WITH MATILDA PILACAPIO

Mongabay: What is your background and how to you come to be involved in your current efforts?

Matilda Pilacapio: Well firstly, I am a landowner from the Sagarai Valley of the Milne Bay province, where Cargill operations palm oil in Papua New Guinea are located.

In Milne Bay, I come from a matrilineal society where women have the upper hand when it comes to land and the environment, and we have a bigger say than men when it comes to land ownership. So I have been very much involved from the beginning.

Mongabay: What's happening in Milne Bay? Is this also occurring in other parts of PNG?

Matilda Pilacapio: Yes for certain. I think it is a disease right throughout the country and the moment and a lot of the land, especially the good land, has been taken up for growing palm oil.

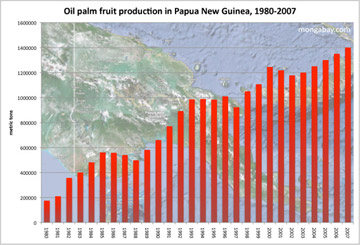

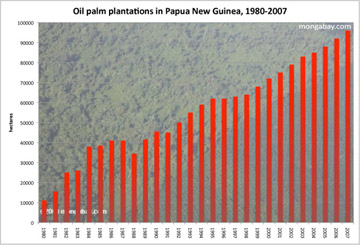

Extent of oil palm plantations in Papua New Guinea from 1980-2007. Data courtesy of FAO

Extent of oil palm plantations in Papua New Guinea from 1980-2007. Data courtesy of FAO |

Cargill really should come down and talk to the people. The people really don't know what a joint venture is—if it is for 20 years, 40 years, 99 years. They don't have a lawyer to explain to them the contents of the agreement. They just say "Come into the office and now you sign there." People don't know better. They just put the silly old signature there. They never see it again until a controversy comes up and everyone is running for lawyers and going to court. And by then it is too late, the deal has been signed already.

The disadvantages and advantages must be spelled out first to the landowners because a lot of our people are still very illiterate. They don't have connections to NGOs, they are far away and the gap is too wide. Before they can reach the NGOs in Pt Moresby it is far too late, the deals have been signs. So that is a big problem, Cargill needs to stop joint ventures and sit down with communities who know about oil palm. At the moment deals are just being signed left and right with Cargill for joint ventures.

Mongabay: What are the alternative activities to generate livelihoods in Milne Bay?

Matilda Pilacapio: What I would like to see is more intercropping. Intercropping means you grow 4 or 5 cash crops on one piece of land. Down below you can also plant root crops like Taro, cacao, yams, and tapioca for subsistence farmers. Because on the world market prices fluctuate, this will bring benefits to the farmer despite the price fluctuations. With palm oil there is only one crop grown on the land and it is useless to the farmers, who can't survive eating only palm oil.

Mongabay: There has recent been a lot of controversy about carbon finance in PNG. What would need to happen to make payments for forest conservation palatable for local communities?

Matilda Pilacapio: We have had a lot of meetings in PNG regarding climate change, carbon trading, and carbon sinks—whatever. It is new language come about in the country. Even our public servants find it hard. I think it was the NGOs, the international NGOs, that brought it down to the local NGOs. We saw it on the Internet and we started bringing it down to the landowners. I talked over it with a couple of landowners and they just didn't know what it was. I told them keep reading the papers; keep listening to the radio, the media will tell you more about it.

What I think should really be done in my country is we really should have legislation in place. There must be laws, bylaws enshrined in out constitution. At the moment there are no laws, no acts, no policy, and should the people start going into carbon trading, they just don't know what money is coming in, who is benefiting, who is the middle man. At one meeting I questioned a group of experts who came over from overseas, and I asked the question: "We saw it happen in the forestry industry with transfer pricing, now I don't want it to be repeated in the carbon trade when it comes to transfer pricing." Because this is something that is a foreign language and our people must know about it. Otherwise it will go the same way as what happened with forestry.

I think our people's rights must be safeguarded with legislation. We don't have any policies in place regarding this carbon trading. It is a new language altogether, we have not heard it in the past. It is not enshrined in our constitution, and therefore we need bylaws to safeguard to what is happen in the future. I believe there are millions of kina or dollars that are going to be put into carbon sinks or carbon trading and our people have yet to know their rights. And my question here is that who is going to be the middleman and who is going to be dishing out the money. And who is going to be benefiting? When it comes to transfer pricing of such monies, which is going to be the one to benefit? My people do not understand the language. If is goes onto a stock market, will my people understand what is happening. Because that is what happened in the forestry sector. We had a lot of controversy with the transfer pricing of logs and our forests, and I do not want it to happen with the carbon trade money.