Noozhawk | 4 October 2023

Carrot boycott over water rights gains traction in Cuyama Valley

In 2022, the amount of groundwater that Bolthouse and Grimmway pumped for carrots was equivalent to nearly a year’s supply for three cities the size of Santa Barbara, population 87,000. Basin-wide, it rains only 13 inches yearly in the valley, on average. GSA records show that over time, more than twice as much water is being pumped out of the basin as is being replenished by rain.

Carrot boycott over water rights gains traction in Cuyama Valley

by Melinda Burns

A carrot boycott that was launched in the Cuyama Valley this summer has galvanized the residents of the remote agricultural region to come together in protest.

In late July, farmers and ranchers kicked off a boycott against the carrot corporations in their midst, two global companies that are roping all 700 valley landowners into an expensive water rights lawsuit. About 150 valley residents attended the launch at the Cuyama Buckhorn.

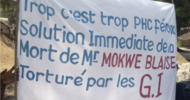

Now, the organizers say they’re having trouble keeping up with the demand for boycott yard signs, bumper stickers and banners, which are posted prominently along Highway 166 and Highway 33. They say they’ve also been swamped with press requests for interviews, from regional media to The New York Times.

The campaign has a Facebook page and a website, StandWithCuyama.com, and claims to have collected more than 7,000 signatures on a petition in support of the boycott — mostly from residents and their relatives — demanding that Bolthouse and Grimmway, global carrot corporations that are by far the largest water users in the valley, stop over-pumping, drop the water rights lawsuit, and reimburse other landowners for the lawyers’ fees they’ve incurred.

On Saturday, residents gathered after the football homecoming game in New Cuyama to pose for a group photo with a StandWithCuyama banner.

“One of the things I hear is how forgotten people feel,” said Ella Boyajian, a boycott organizer who owns a cattle ranch at the western end of the valley. “That lawsuit was a violation, almost, of the philosophy out here where people are good neighbors. It was a real breach of that neighborliness and created this huge sense of frustration.”

The Drawdown

It’s a tough proposition, taking on Bolthouse and Grimmway, the largest carrot producers in the world. But the stakes are high. Groundwater wells are the only source of water here, and underground water levels are in steep decline.

“I think the difficult thing for all of us to wrap our heads around is, we’ve never had corporations outwardly come straight out and attack us,” said Charlie Bosma, a retired sheriff’s deputy who owns a cattle ranch and orchard near New Cuyama.

“They’ve been farming in this valley for decades and depleting the water table consistently as the biggest users of water. We knew that. But we never expected they could do that type of damage to our water table and then turn around and sue us. We’re not going to be OK with this type of bullying.”

Bosma said he’s had to pay $11,700 in legal fees to defend his water rights to date. The lawsuit, which was filed in 2021 in Los Angeles County Superior Court, has finally been set for an initial trial on Jan. 8. It was postponed in August because 243 valley landowners in four counties did not file a response when notices were mailed to them.

Now, as notices are being attached to stakes, residents have reported finding the stakes posted miles from the right address or blown over in the wind, leaving the envelopes strewn along dirt roads and highways.

Water rights “adjudications,” as these lawsuits are called, can drag on for years.

Court records show that 30 law firms and government agencies are representing more than 90 valley landowners against Bolthouse and Grimmway, including cattle ranchers, dairy farmers and pistachio, apple, olive, vegetable and grape growers, plus the local school district, three small water companies and several government agencies. The legal fees paid by the landowners to date likely total hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Santa Barbara County Supervisor Das Williams, who represents the Cuyama Valley, sent out a recent newsletter to his constituents, urging them to support the carrot boycott.

“It’s a way Cuyama residents are trying to reclaim their power, and I always encourage people to live their values through the pocketbook,” he said.

Bolthouse and Grimmway produce carrots of all shapes and sizes, including bunch carrots, shredded carrots, crinkle-cut carrots, mini carrots and carrot juice. They created the wildly popular baby carrot market, triggering the massive expansion of carrot farming in the Cuyama Valley beginning in the 1990s. Grimmway sells carrots under the Bunny-Luv and Cal-Organics brands.

The boycott is aimed at supermarket carrots, Boyajian said.

“If they’re in a supermarket, chances are they’re Bolthouse and Grimmway,” she said. “It’s best to buy carrots in a farmers market if you can.”

A “Collaborative Process”?

The Cuyama Valley groundwater basin is immense, covering 380 square miles in four counties — Santa Barbara, Kern, San Luis Obispo and Ventura — but it’s not infinite.

For 80 years, farming operations — first, mainly alfalfa, and now, mainly carrots — have drawn down the underground water supply. Today, Cuyama’s groundwater basin is on the state list of 21 basins in “critical overdraft.” The rest are in the Central Valley.

Bolthouse and Grimmway’s lawsuit follows on the heels of a mandatory 5% pumping reduction that went into effect in March. For now, the cutbacks are limited to the flat central area of the valley, where Bolthouse and Grimmway own or lease more than half the land, and where the underground water table is lowest.

The pumping reductions are slated to increase to 6.5% yearly in 2025. Under the state Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014, the Cuyama groundwater basin must be back in balance by 2040.

“The government provided us a democratic process to deal with this,” Bosma, the retired sheriff’s deputy, said. The lawsuit, he said, was “a battle none of us needed and none of us can afford.”

Representatives of Bolthouse and Grimmway helped draft the schedule of cutbacks as members of the Cuyama Basin Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) board, made up of county officials and major landowners. By filing a lawsuit, they are now effectively asking a judge in Los Angeles to determine how much water each landowner in the valley is entitled to.

The GSA board, of which Supervisor Williams is a member, holds public hearings in the valley and consults with a citizens’ advisory committee that includes small water users. But, Williams noted, the court proceedings under the water rights adjudication will have “no public input.”

“Folks are just being required to spend countless dollars on lawyers to represent them or risk losing their water rights,” he said.

The Bolthouse Land Co., a subsidiary of Bolthouse Properties, is a plaintiff in the lawsuit alongside Grimmway Enterprises Inc. and its farm management companies. Bolthouse and Grimmway are headquartered in Bakersfield; they are both owned by private equity firms.

Grimmway officials did not respond to a reporter’s request for comment on the lawsuit or the carrot boycott. In a written statement, Dan Clifford, vice president and general counsel for Bolthouse Properties, declined to comment on the boycott but said it was a “common misconception” that Bolthouse Land and Grimmway have “sued” Cuyama Valley landowners.

It’s not a typical lawsuit “where you have plaintiffs and defendants who are truly adverse to each other,” Clifford said. “ … Here, all water users in the basin must be named as a party to the adjudication so that they can establish their right to pump groundwater.”

Clifford called the adjudication “a collaborative process” and said that, early on, representatives of Bolthouse Land “voluntarily met” with “significant water users” and invited them to work things out through a streamlined process, under court supervision, to avoid going to trial.

“Unfortunately, that offer was either ignored or rejected,” he said.

Who Should Cut Back?

In 2022, the amount of groundwater that Bolthouse and Grimmway pumped for carrots was equivalent to nearly a year’s supply for three cities the size of Santa Barbara, population 87,000. Basin-wide, it rains only 13 inches yearly in the valley, on average. GSA records show that over time, more than twice as much water is being pumped out of the basin as is being replenished by rain.

In court, Bolthouse and Grimmway are expected to argue that the pumping reductions should generally apply to farmers throughout the basin and not be confined to the central area, which accounts for about two-thirds of the water use in the valley.

“The only way the basin, as a whole, will be brought into sustainability is if the cutbacks are borne equally by all of the groundwater users in the basin — de minimus users excluded — not just in a single area, as the plan currently contemplates,” Clifford said. “Pumping reductions in the Central Management Area, only, will not result in the basin being sustainable.”

De minimus water users are those who pump less than one acre-foot of water per year, Clifford said, adding: “We aren’t trying to cut back the mom-and-pop users, the single family residences with some chickens, livestock and a small garden.” In addition, he said, “the lawsuit does not seek to determine rights to municipal water service” in the valley.

Bolthouse Land “isn’t trying to get a better deal through the adjudication,” Clifford said. The company, he said, “intends to remain a corporate citizen in the basin for many decades to come, and damaging the aquifer is at odds with that reality.”