Mongabay | 17 January 2024

Outcry over deforestation as Suriname’s agriculture plans come to light

by Maxwell Radwin

Possible plans to develop large-scale agriculture in Suriname have sparked backlash from Indigenous communities, conservation groups and some members of parliament, who are concerned about deforestation of the Amazon and the fate of ancestral territories.

Government documents, first published by Mongabay last year, showed that hundreds of thousands of hectares of Suriname’s primary forest might be under consideration for agriculture. Now, voices from all over the country are speaking out against it.

“The government doesn’t communicate with the people in the forest. They don’t care about the well-being of the communities,” said Hugo Jabini, a human rights lawyer and member of the Saamaka tribe, which relies on the country’s forest for hunting and fishing. “They only focus on their own political benefit, their own family, their own economic interests.”

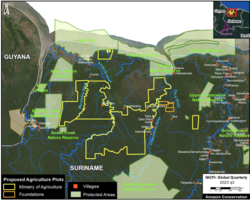

Mongabay originally reported that approximately 354,836 hectares (876,819 acres) of land were being considered for agricultural use, requiring huge swaths of the rainforest to be cut down. But a new report from Monitoring of the Amazon Project (MAAP), performing a more rigorous analysis of Mongabay’s data, found that the area under consideration could be even larger than that — around 467,000 hectares (1,153,982 acres), of which 451,000 hectares (1,114,445 acres) is primary forest.

It would be a shocking amount of deforestation, the report noted, for a country that has had an annual deforestation rate of just 6,560 hectares (16,210 acres) over the last two decades, some of the lowest on the continent.

The map shows several local and Indigenous communities located within or on the border of the government’s alleged development plans. Several protected areas are also close by, including the Kaboeri Kreek Nature Reserve, Snake Creek Nature Reserve, Nanni Nature Reserve, Peruvia Nature Reserve and Central Suriname Nature Reserve.

Suriname is the only country in South America that hasn’t formally recognized Indigenous land rights, with current legislation stalled in parliament. Communities are now starting to worry that agricultural development will mean the end of those efforts.

“We are threatened with land theft, clear-cutting of forests, loss of biodiversity and environmental destruction,” said the Association of Indigenous Village Heads in Suriname (VIDS) in a statement. “The important livelihood opportunities of the first inhabitants of Suriname are being taken away from us, and there is fear for our safety.”

It added, “VIDS finds it unacceptable that large areas of land are currently being allocated for large-scale agricultural purposes.”

The Office of the President and Ministry of Land Policy and Forest Management didn’t respond to a request for comment for this story.

A petition, directed to the President of the Republic of Suriname, was launched this month to raise awareness and stop agricultural development from moving forward. “We will lose the potential of earning up to $2 billion annually for the carbon storage and absorption services that our forest provides,” it said.

Suriname is around 93% primary forest, allowing it to be one of the only countries in the world with a carbon-negative economy, meaning it absorbs more carbon dioxide than it emits. But food scarcity and high poverty rates have put pressure on the government to develop new revenue streams, agriculture being one of the most attractive.

Local land developers are trying to scale up their projects in preparation. Mennonites are in talks with the government to relocate to Suriname and set up farms. Their history of aggressive expansion and deforestation — most notably in Mexico, Belize and Bolivia — is a major concern for conservation groups. They’re known for buying up land at a rapid pace.

“I call for an urgent investigation into the actions of the Minister of Land Policy,” Rabin Parmessar, a member of parliament, said last week. “It’s the first time in history that a minister of land affairs has been involved in so many allegedly corrupt land allocations.”

He added, “It’s reprehensible that foreigners are eligible for hectares of land, while our own countrymen wait for years for a square meter to do horticulture and agriculture.”

Parmessar told Mongabay he’s frustrated with the lack of transparency from ministry officials, who are supposed to speak to parliament about development plans later this week during budget talks.

Indigenous groups are still in the process of organizing resistance efforts. The Maroon Awareness Platform, an umbrella organization representing afro-descendent groups in Suriname, told Mongabay the government doesn’t communicate with them, which means they are often the last ones to know what’s happening, let alone to mount a response.

The Saamaka community, although not directly impacted by the land included in government mapping obtained by Mongabay, said it’s considering presenting a case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Costa Rica, which takes on issues related to human rights violations in Latin America.

“The world will know the role this government is playing in all of this,” Jabini said. “When they show up to international forums talking about Suriname being the greenest country, everyone will know that is a big lie, because their actions are different from what they’re saying.”