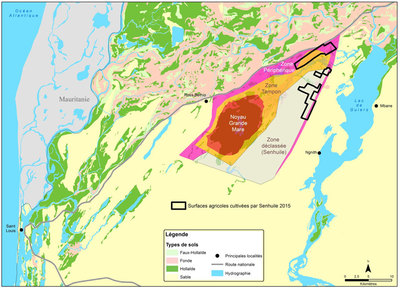

Senegalese agro-pastoralists are striking wins against Senhuile SA, a foreign-owned agribusiness company established in Ndiaël, Saint-Louis Region of Senegal. In 2012, Senhuile obtained a 50 year lease on 20,000 hectares for a sweet potato plantation in a forest and wetland reserve, which was partially declassified to establish agribusiness activities.1 The deal threatened 9,000 pastoralists, who depend on these lands for their livelihoods. In addition to grazing their 100,000 animals (cows, sheep, goats, and horses), these lands also provide them with firewood, fruits, medicinal plants, and saps and resins.

Ndiael - Les Populations Réclament Leurs Terres par miroironlinegb

For over four years, 37 villages impacted by Senhuile’s activities have shown fierce resistance. In the latest action, over 350 local opponents to the project gathered on July 29, 2016, to claim their right to farm the reserve lands. Previously, communities had been denied the authorization to cultivate small plots on the grounds that Ndiaël was classified among the Ramsar Wetlands of International Importance. Now that large tracts of the reserve have been declassified and cleared by Senhuile, residents of Ndiaël are determined to start their own agricultural activities in the area.

Prior to 2012, Senhuile had planned to settle in Fanaye, some 30 kilometers away, but was forced to relocate after violent local opposition led to the deaths of two protestors and injuries to many others in 2011. Upon arriving in Ndiaël, Senhuile did not seek the consent of the local communities or provide compensation for the loss of grazing lands. Instead, it carried out aggressive land clearing—religious spaces, cemeteries, schools were destroyed in the process—while protecting its concession with barbed wires and security guards.

Senhuile: Lack of Transparency & Scandals

Senhuile’s project has been opaque since its inception. Although located in a semi-arid area with plans for large-scale irrigation using water from the adjacent Lake Guiers—a crucial reservoir already affected by low water levels, algae proliferation, and pollution—Senhuile conducted its first environmental impact assessment only months after starting to clear the land. The company initially announced its intention to grow sweet potatoes for bioethanol production, but its strategy shifted several times, from sunflower plantations to finally opting in 2016 for rice, maize, and peanut production.

In addition, Senhuile has been involved in scandals repetitively. Held by a murky international conglomeratecomposed of Italy's Tampieri Financial Group, Senegalese investors, and a shell company registered in New York, Senhuile has changed directors three times since 2012. Benjamin Dummai, its first CEO, was arrested in 2014 on charges of misappropriating CFA 200 million (over $300,000). Dummai’s successor, Massimo Castelluci, fired a large number of employees. Dismissal-related disputes are now opposing Senhuile in the regional Saint-Louis Court. In July 2016, Senhuile’s latest director, Massimo Vittorio Campadese, barely avoided prison after the company was accused of committing customs fraud and negotiated a CFA 1.1 billion ($1.85 million) fine to settle the matter.

Senhuile’s disastrous track record belies the company’s intentions and initial claims around its contribution to the local economy – Senhuile promised to create 2,500 jobs by 2013 but today employs less than 100 people. Unsurprisingly, initial resistance from the 37 villages impacted by the project has garnered strength as former Senhuile workers and neighboring rice growers, who were recently expropriated from lands previously granted to them by the company, have joined the opposition.

Senegalese authorities, consequently, have been forced to recognize the legitimacy of the local resistance. A few months ago, they announced—and recently confirmed—their intention to reduce Senhuile’s concession by half from 20,000 to 10,000 hectares. The recent mobilization was organized by local communities to build on this successful development. They are claiming their right to over 14,000 hectares of lands in the reserve, including all of Senhuile’s former lands and some other declassified areas. This action has served as a successful catalyst to kick-start a negotiation process in August 2016 between the Senegalese administration, the company, and protestors to demarcate and divide the declassified lands for redistribution.

The residents of Ndiaël hope to soon start using the land for cultivating cash crops including watermelons, sweet potatoes, and cassava. Cattle herding, the area’s traditional occupation, will accompany agricultural activities. Small-scale agricultural plots, contrary to large-scale farms, leave space for cattle routes and preserve animals’ access to water points. In addition, after harvesting, farmers will let the cattle graze leftover fodder from the fields and use the manure to fertilize the soil. These methods of small-scale agriculture will respect the zone’s ecology, feed entire families, and invigorate the local economy.2

While the expectations are high, the struggle isn’t over for the community members. They are still waiting for proper land demarcation and fear unexpected developments, including allocations of concessions to firms participating in the World Bank-funded Inclusive and Sustainable Agribusiness Development Project (PDIDAS). However, their tenacious resistance has voiced an honest appeal to the government to prioritize the future and food security of Senegalese families over the interests of foreign investors. If villagers win, the Ndiaël case may set a precedent for other populations affected by land grabbing in the country. If not, they are ready to scale up the resistance. As local opponent Ardo Sow explains, “this is a fight for survival. We cannot remain bystanders and watch the state run roughshod over the population. […] We will not cede for anything in the world.”

Footnotes

[1] The declassification of 20,000 hectares of reserve land for a large-scale agriculture project was surprising considering that, in March 2012, the same month former President Wade issued the decree granting land to Senhuile, the Senegalese government submitted an official financing request to the World Bank for a project to restore the Lac de Guiers area and adjacent wetland ecosystems, particularly the Ndiaël reserve, considered an endangered Ramsar site.[2] Surveys conducted in the area have found that small farms obtain excellent profits from their commercial activities (notably potato and rice cultures) and employ a great number of workers.