Southeast Asia is world's hotspot for land disputes: report

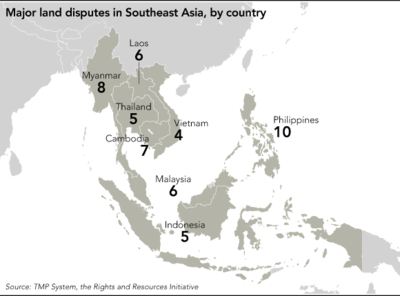

Out of a sample of 51 major land disputes surveyed across the region, all but 6 remain unresolved, meaning that Southeast Asia is the region most prone to land conflict in the world. That is according to research published Tuesday by UK-based consultancy TMP Systems and the Rights and Resources Initiative, a global coalition of land rights activists funded in part by the British and Norwegian governments.

That 88% of land disputes in Southeast Asia are not resolved puts the region above the 61% global average, according to the research, which covers land disputes dating from 2001.

The costs for businesses embroiled in such disputes can be significant: In the 51 Southeast Asian cases studied, 65% saw the companies involved incur financial losses. Other high-profile projects, including many not covered in the TMP/RRI research, have been delayed over land acquisition challenges -- such the Jakarta-Bandung high speed rail link, central to the Indonesian government's lavish infrastructure modernization plans.

"There's a hard-headed argument in financial terms that companies are much better off to avoid these conflicts at all costs," said Ben Bowie of TMP Systems.

As well as infrastructure developments, the types of businesses caught up in such disputes include agriculture -- sugar plantations linked to powerful politicians in Cambodia and palm oil plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia -- as well as mining in the Philippines, and infrastructure projects in Myanmar, among others.

Border issues

Many of the disputes take place in peripheral or border areas of countries -- an average distance of only 33km from a frontier. Projects in these liminal regions are often fast-tracked by eager businesses rubber-stamped by corrupt local officials, as rule of law tends to be weaker than in central regions or close to major cities, generating "a perceived sense of impunity," according to Bowie.

In some cases, border regions are inhabited by ethnic minorities or overlap with special economic zones created by governments where low tax rates and other incentives are offered to attract investment.

But conflicts arise due to lack of clarity on land tenure and because in some cases, such as decentralized Indonesia, there are contradictory laws at national and local levels.

In countries such as Laos, a one party state that brooks no political dissent and where court systems are nascent, there is little scope for redress. "Governance is one of the many factors that feeds into a complex framework of disputes," said Bowie.

In military-ruled Thailand, recent decrees on special economic zones have seen land expropriated in border regions close to Cambodia and Laos.

And where tightly controlled or authoritarian states push through projects, the lack of transparency and dismissal of residents' rights sometimes "creates the conditions for an uncontrollable dispute," Bowie said.

Intractable disputes

Such dynamics likely account for some of Southeast Asia's long-running and seemingly intractable land disputes, which have put businesses out of pocket and unable to get beyond planning stages.

Across the region, farming is often the main source of income for a significant proportion of the population: 12% in Malaysia, 29% in the Philippines, 32% in Thailand, 33% in Indonesia, 44% in Vietnam and 54% in Cambodia, according to International Labour Organization data. Estimates put the comparable figure for Myanmar at around 70%.

Disputes have left farmers landless or shunted away to smaller holdings with sometimes paltry compensation, sufficiently aggrieved and motivated to prevent projects from going ahead or to continue to fight years later.

In Cambodia, villagers who were forcibly pushed off their land in Koh Kong province a decade ago to make way for a sugar plantation, travelled to capital Phnom Penh to protest as recently as late August, resulting in clashes with police after government officials refused to meet the group.

Displacement -- forcing residents off their land -- is the main driver of disputes in this part of Southeast Asia, accounting for 43% of cases, the same percentage of disputes in the region that turned violent, including fatalities in a fifth of cases in the last 15 years.

Indeed data from around the region suggests that land disputes are a wider problem than shown by the cases covered in the TMP/RRI research. By March 2016, a Myanmar parliamentary commission looking into land issues dating back to 1988 had received 17,000 complaints from the public in a country where the army and associated businessmen, or "cronies," had a long history of taking whatever land they wanted in a resource-rich country.

Risk to reputations

On mainland Southeast Asia -- Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam -- disputes last an average of 8.9 years and of those documented since 2001, only 10% have been resolved, while across Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, the percentage of resolved land disputes is only a notch higher, at 14%.

In Indonesia, palm oil companies have been vilified internationally -- enduring what is known in business circles as "reputational risk" -- for their alleged role in deforestation and in health hazard forest fires as Indonesia's oil palm production expanded from 5 million tons a year in 1997 to 33 million tons by 2014.

Palm oil companies have responded by pledging to harvest and produce only "sustainable" palm oil and have joined in government efforts to stem land and forest clearances, usually by burning, which send a thick choking haze across the Strait of Malacca from Sumatra in Indonesia, covering parts of Malaysia and Singapore for weeks on end.

The high-profile international campaigns around land disputes in Indonesia -- which have been linked to the endangering of species such as the Sumatran tiger and orangutan -- has contributed, it seems, to activists' successfully stalling unwanted projects, often by bypassing local courts and officials.

As the TMP/RRI research noted, "in March 2017, seven Papuan NGOs released a declaration advising that affected communities and civil society organizations should try to reach legal settlements without going through the courts and should engage in local, regional, national, and international advocacy campaigns."

Such activism might be paying off, albeit slowly, with the Indonesian government promising to extend customary land rights across the archipelago and give greater legal clarity to landholders and would-be investors.

Discussing the government's pledge, Arifin Saleh Monang, a farmer from North Sumatra in Indonesia, whose land was seized to make way for a palm oil plantation, said "so far it is an unfulfilled commitment."

But companies are now more sensitive to the image damage incurred by being associated with environmental damage and land grabs.

"There is also an increasing understanding of practical steps a company can take -- like more detailed land due diligence before land is acquired or by working through other business models that don't rely on outright acquisition," said Jeffrey Hatcher of Indufor Group, a forest management consultancy.